When pondering the enigmatic allure of Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, one cannot help but be captivated by the presence of the formidable moai statues. These monolithic figures, representative of the island’s rich cultural heritage, are an indelible part of its mystique. A compelling question arises: how old are these iconic statues, and what does their age reveal about the island’s ancient civilization? This inquiry not only invites exploration into the dating methodologies employed but also challenges our understanding of Rapa Nui’s historical narrative.

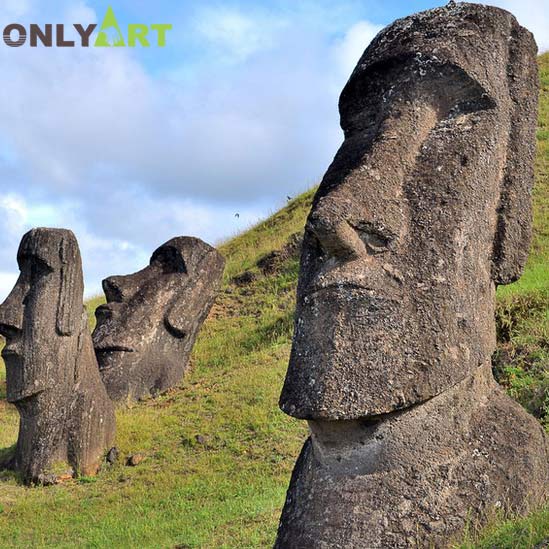

The moai statues, crafted primarily from volcanic tuff, vary in size, with the tallest reaching nearly 33 feet and weighing upwards of 75 tons. Their monumental scale speaks to the sophisticated artistry and labor organization of the Rapa Nui people. Initially believed to be erected in honor of deceased ancestors, these statues represent an amalgamation of profound spiritual and sociopolitical significance within the community.

To ascertain the age of the moai, researchers employ a multifaceted approach, intertwining archaeological stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating, and analysis of historical records. Stratigraphy, the study of rock layers and their sequence, provides insight into the temporal context in which the statues were created. When excavations reveal layers associated with the moai, archaeologists can establish a relative chronology that helps date their construction.

Radiocarbon dating, a pivotal technique in archaeology, applies to organic materials within the strata. By measuring the decay of carbon isotopes in associated organic remnants, such as charcoal from ceremonial fires, scientists can form a nuanced timeline. Radiocarbon dating of associated artifacts suggests that the moai were sculpted primarily between 1400 and 1650 CE. However, certain conjectures propose that the tradition may have begun even earlier, potentially as far back as 800 CE. This divergence in dating signifies the need for careful interpretation of methods and results.

Complementing the empirical data, historical accounts from European explorers visiting Easter Island in the 18th century offer additional context. Despite the limitations of these records, they highlight the prominence of moai in Rapa Nui society, capturing observations of the island’s cultural practices. For instance, Captain James Cook’s expeditions in the 1770s noted the moai, stating their significance as symbols of power and reverence. These narratives, although not precise, contribute to the tapestry of understanding regarding the importance of the moai to the Rapa Nui populace.

Another critical factor in comprehending the age of the moai is the evolution of the island’s environment and how it influenced the construction and maintenance of these statues. The deforestation of Rapa Nui, primarily due to resource overexploitation and agricultural demands, has been linked to the waning of the moai-building tradition. This environmental decline may have commenced alongside the initial carving of the statues, suggesting a complex interrelation between human activity and ecological consequences. Thus, the chronological layering of the moai cannot be disentangled from the ecological narrative of the island.

Nevertheless, while presenting a timeline offers significant clarity, the question arises: how did variations in the construction techniques influence the dating of the statues? The moai were not uniformly created; differing styles and sizes reflect shifts in artistic expression over time. Some moai exhibit features indicative of earlier traditions, while others represent a culmination of sculptural innovation. This stylistic evolution complicates the straightforward attribution of a singular age to all moai and necessitates further examination of these artifacts as dynamic symbols of cultural identity.

The socio-political dimensions surrounding the moai also demand consideration, particularly in regard to the societal structures that facilitated their construction. Theories suggest that the practice of moai carving may have been a communal endeavor, emblematic of an egalitarian society capable of mobilizing labor. In contrast, the eventual decline of moai construction reflects a transition towards social stratification and competition for resources. This transformation raises poignant questions about the sustainability of the moai tradition and its correlation with societal shifts over centuries.

Ultimately, while current research suggests that the majority of moai were created between 1400 and 1650 CE, the challenge remains to reconcile this timeline with the intricate socio-ecological narrative of Rapa Nui. Furthermore, the question of how these monumental figures were transported across the island requires a nuanced understanding of ancient engineering and cooperative labor strategies, underscoring the complexity surrounding their legacy.

In summary, the age of Easter Island’s moai statues is just one facet of a broader narrative encompassing cultural significance, innovative artistry, and environmental dynamics. As modern archaeological techniques evolve, so too does our comprehension of these legacies—offering fresh insights into the interplay of history, culture, and ecology. Therefore, while the moai may stand sentinel over Rapa Nui, they also evoke a continuous dialogue about the past and the lessons that remain relevant in contemporary discussions about sustainability and cultural preservation.