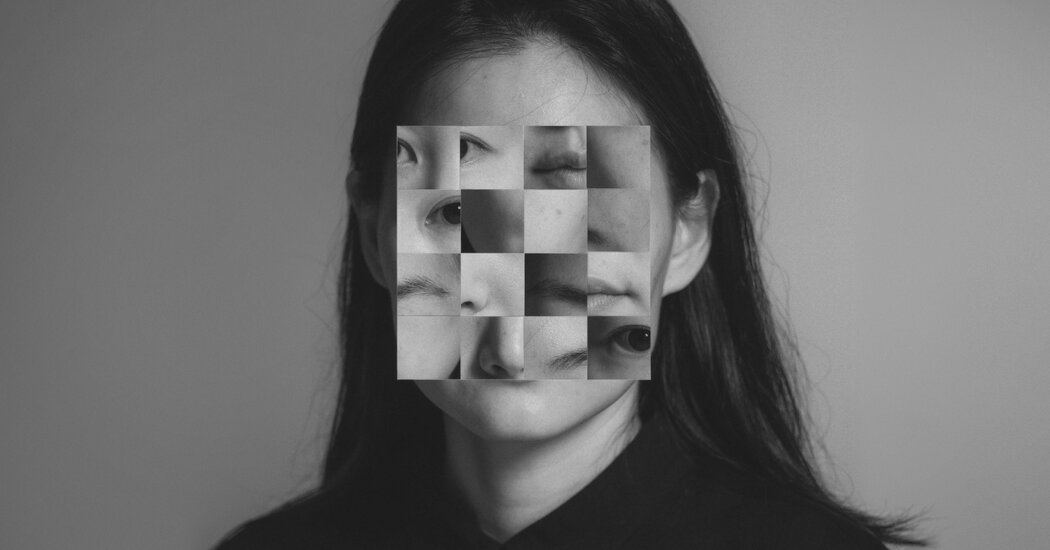

In contemporary discourse surrounding race and ethnicity, the classification of different groups has elicited considerable debate, particularly concerning the categorization of Asians as Persons of Color (POC). This classification is intrinsically tied to cultural relativism, which posits that the significance of racial identity is contingent upon contextual and cultural frameworks. This article embarks on a thorough examination of how Asians are perceived in the socio-political landscape of identity and classification through the lens of cultural relativism.

To begin with, it is essential to demarcate the term ‘Persons of Color.’ Generally, this term encompasses individuals who are non-white and whom society often marginalizes due to their ethnicity or racial identity. This definition raises immediate queries about the categorization of Asians, a group that is extraordinarily diverse, comprising myriad ethnicities, cultures, and historical backgrounds. Are they included in the broader spectrum of POC, or do their experiences and histories place them in a different category altogether?

One should acknowledge that racial classification is not solely a biological phenomenon; rather, it is a social construct shaped by historical, political, and economic factors. In the United States, the historical context of race relations plays a significant role in how Asians are perceived and classified. The model minority myth—a stereotype suggesting that Asian Americans are inherently successful—complicates racial dynamics and leads to divergent perceptions of identity within the Asian demographic.

The complexities of identity are further compounded when considering sub-groups within the Asian community. For instance, South Asians may resonate more closely with the experiences of discrimination faced by Black Americans, while East Asians might have a different racial narrative shaped by socio-economic mobility and the aforementioned model minority stereotype. This complex interplay demands a nuanced understanding of how these groups negotiate their identities in varying contexts, thus reinforcing the argument for cultural relativism.

From a cultural relativism perspective, it is paramount to recognize that identity is fluid and often contextual. The question of whether Asians are categorized as POC may vary based on geographical, historical, and social nuances. In an American context, political movements and dialogues surrounding race have increasingly sought to include Asian voices in discussions about discrimination, equity, and justice. Social movements advocating for racial justice, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, inherently invite Asian Americans to participate in a broader coalition that seeks to dismantle systemic racism.

Moreover, the repercussions of recent events—such as the rise in anti-Asian sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic—have underscored the necessity for a unified front against racism, thereby reinforcing the classification of Asians as Persons of Color. Such incidents have highlighted that, despite historical narratives suggesting high socio-economic status among Asians, they too can face prejudice and discrimination, urging a reevaluation of identity and classification in contemporary society.

However, it is pertinent to consider the duality of this classification. While many may identify as POC, this self-identification can evoke feelings of dissonance within certain circles of Asian communities, particularly amongst those who have benefitted from racial privilege. This discrepancy illuminates the complex layers of identity and allows for a discourse on intersectionality, where individuals may occupy multiple identities that influence their experiences of privilege and oppression.

Intersectionality further complicates classification, as individuals often navigate multiple identities concurrently. For instance, a queer Asian individual may encounter unique struggles shaped not only by their racial identity but also by their sexual orientation. Such experiences signal the limitations of traditional racial classifications, proving that identity cannot be encapsulated within rigid frameworks.

Additionally, cultural relativism emphasizes the importance of acknowledging the individual narratives within larger ethnic categories. The Asian American experience is not monolithic; it is shaped by various factors, including immigration status, socioeconomic background, and generational differences. This recognition is crucial for fostering dialogues that are inclusive and representative of multiple voices within the Asian community.

The growing discourse around racial identity serves as a catalyst for critical discussions about representation and inclusion. As discussions surrounding POC identities evolve, Asian voices increasingly assert their place within these narratives. Awareness campaigns and academic research dedicated to amplifying Asian experiences highlight the ongoing struggle against racial stereotypes and systemic inequality, contributing to a broader understanding of what it means to navigate life as a Person of Color.

Moreover, the implications of classifying Asians as Persons of Color extend beyond individual experiences; it influences policy initiatives, community organizing, and educational reforms. Legislators and community leaders are recognizing the significance of representing Asian Americans in conversations about equity, thereby challenging the historically privileged narratives that have dominated discourse around racial classification.

In conclusion, the classification of Asians as Persons of Color is a multifaceted topic that transcends simplistic categorizations. Through the lens of cultural relativism, one comprehends the diversity and complexity within the Asian community, recognizing that identity is not merely an academic classification but a lived experience. As societal attitudes continue to evolve, so too will the conversations surrounding racial identity, highlighting the need for ongoing dialogue and reflection.