Are humans a type of ape? This provocative inquiry challenges us to reconsider our perceptions of what it means to be human. Within the realm of evolutionary biology, the classification of humans as members of the family Hominidae is well-established. This family includes not just Homo sapiens, but also our close relatives such as chimpanzees and gorillas. This ancestral connection invites a deeper examination of cultural relativism and how our understanding of humans as a type of ape can influence societal norms and values.

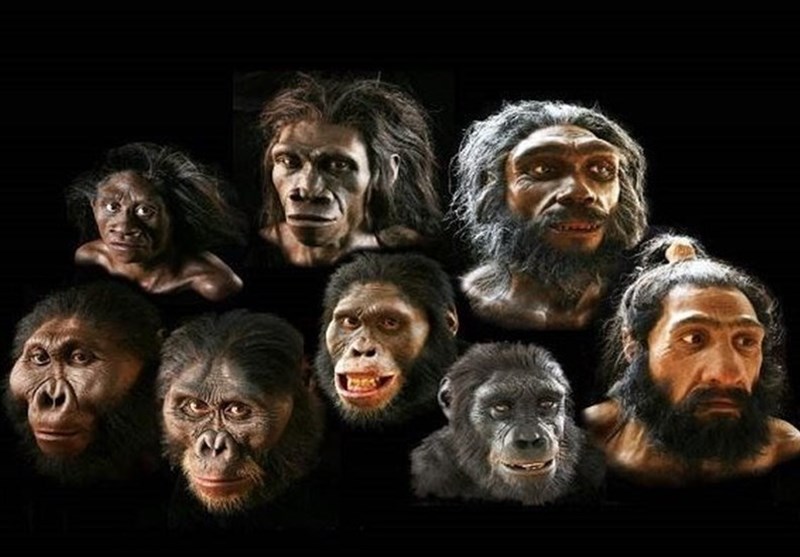

To unravel this intricate tapestry, it is essential to define both the biological classification of humans and the cultural implications intertwined within it. The Hominidae, or great apes, consist of four extant genera: Homo, Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo. Deeply rooted in shared ancestry, both humans and chimpanzees diverged from a common ancestor approximately six to seven million years ago. Such evolutionary kinship poses significant questions regarding our cultural practices and the very tenets of what we deem to be ‘human’.

Cultural relativism, on the other hand, posits that one’s beliefs and practices must be understood within their own cultural context. Within this framework, the classification of humans as apes unveils potential biases embedded within societal perceptions of superiority and distinction between species. If we accept the premise that humans are merely a subset of the vast ape family, how does this reshape our understanding of human culture, morality, and identity?

Concomitantly, the distinction between ‘human’ and ‘ape’ often arises from specific sociocultural constructs. Historically, such constructs have unveiled the unsavory sides of human behavior leading to ethnocentrism, whereby people evaluate and judge cultures through their own values. This perspective has frequently marginalized or devalued non-Western cultures, often branding them as primitive or less advanced. However, if humans are indeed a type of ape, then differentiating between cultural practices based on arbitrary social standards becomes a fundamentally flawed exercise.

One must consider the implications of acknowledging our shared ancestry with apes on issues such as conservation and animal rights. The familial ties we share with other primates have catalyzed ethical debates surrounding the treatment of non-human animals. This evolutionary connection fosters a sense of kinship that, when embraced, encourages a more compassionate approach towards conservation efforts, especially for endangered species such as orangutans and gorillas. Consequently, recognizing humans as one species among many in the ape lineage can amplify advocacy for preserving their habitats and ensuring their survival.

Moreover, this evolutionary lens reorients our approach towards anthropological research. When researchers position humans within the broader context of the great apes, it allows for a comparative analysis of behaviors and social structures. For instance, examining the complex tool use among chimpanzees or the cooperative hunting strategies in orangutans elucidates the rich tapestry of life shared within the ape family, blurring the lines we often draw between species.

Curiously, the linguistic abilities of humans—often heralded as a defining trait—serve as further touchstone in this discourse. Language itself is a sophisticated tool for social interaction, one that is not solely limited to humans. Many primate species employ vocalizations and gestures to convey information, thereby drawing attention to the evolutionary roots of communication. If we consider language as an evolutionary trait rather than a privilege exclusive to humans, we can begin to appreciate various forms of expression across species, thus enriching our understanding of social dynamics in the animal kingdom.

As we delve deeper into the cultural implications of identifying humans as a type of ape, we confront the nuances of morality and ethical behavior. Many anthropologists argue that moral frameworks are, to a degree, an evolutionary adaptation built on social cooperation. By understanding our behaviors through the lens of cultural relativism, we can discern that moral codes are not universally applicable; rather, they are products of specific sociocultural environments. This realization prompts a reconsideration of moral superiority and efficacy across different human societies.

It is pivotal to recognize the potential divergences and convergences among ape species in response to environmental pressures. Such variations challenge the presumption of humanity’s unique grasp on morality and social organization. For example, matrilineal societies in certain primate communities exhibit strong kinship bonds echoing themes within many human cultures, while also presenting alternative frameworks for social structures. This acknowledgment may foster greater tolerance and understanding of alternate social systems worldwide.

This exploration into the conceptualization of humans as a type of ape does not presume purity in our cultural practices, but rather encourages conscious reflection on our actions. It beckons a challenge to recognize that superiority is often a construct that serves to disconnect us from our natural heritage. By embracing this shared ancestry, there lies the promise for a more profound empathy towards both human and non-human cultures alike, as we navigate the intricate mosaic of shared existence on our planet.

Ultimately, the question of whether humans are a type of ape serves as more than an inquiry into biological lineage; it is a portal into understanding the nature of humanity itself. By bridging the chasms between species, we can glean deeper insights into cultural relativism and advocate for a harmonious coexistence that celebrates the diversity of life. The playful query, therefore, reveals the profound complexities of our identity, urging us to reevaluate implications of kinship that stretch across the annals of evolutionary history.