The 1600s represent an intriguing era in the tapestry of human history, particularly in the realm of life expectancy. To assess how long individuals lived during this period necessitates an interdisciplinary approach that intertwines demographic data with cultural relativism. It is critical to recognize that life expectancy figures are not simply numerical values; they encapsulate the wider sociocultural milieu and the unique circumstances of different populations. Understanding life expectancy through the lens of cultural relativism allows us not only to comprehend the past more thoroughly but also to glean insights that resonate with contemporary societies.

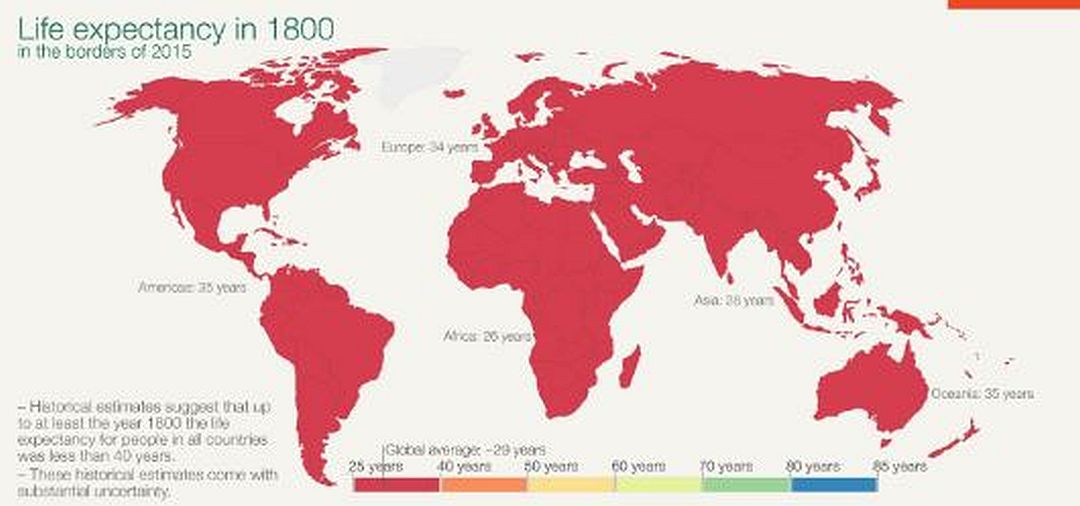

During the early decades of the 17th century, life expectancy varied significantly across geographic regions, social strata, and cultural contexts. In Europe, for instance, historical records suggest a life expectancy at birth of approximately 35 years, although this figure often masks the cruel realities of high infant mortality. Many who survived childhood could expect to live into their 50s or even 60s, illuminating the stark divisions in life outcomes based on age and health at various life stages. The stark contrast of life expectancy between the elite, who had access to better nutrition and medical care, and the peasantry, who were subject to harsh living conditions, accentuates the societal inequities prevalent during this time.

Examining life expectancy through the lens of cultural relativism permits an appreciation for how local customs, beliefs, and environmental influences dictated longevity. For example, the agrarian lifestyle of peasants led to a dependence on seasonal crops, inundating their diets with a plethora of vitamins and minerals essential for health; however, the cyclical nature of food availability could also result in periods of scarcity and malnutrition. In stark contrast, nobility often possessed the privilege of varied, nutrient-rich diets, reflecting a broader global disparity in health outcomes.

Moreover, the sociopolitical landscape of the 1600s cannot be disregarded when analyzing life expectancy. The tumultuous context of wars—such as the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648)—and the socioeconomic impact of plagues such as the Bubonic plague that recurred intermittently throughout Europe significantly curtailed life expectancy. The average lifespan offered by formal statistics fails to capture this volatility; it merely reflects averages obscured by societal chaos. Therefore, this perspective unveils an arrive at a deeper understanding of the collective suffering endured by populations during moments of strife.

Furthermore, cultural attitudes towards health and mortality shaped individual lifespans. Many societies viewed death as an integral aspect of life, which, while somber, imbued their understanding of life expectancy with a unique philosophical depth. This perspective can be seen in the literature and art of the period, which often grappled with mortality in profound ways. Shakespeare’s works, for instance, are replete with reflections on life’s transience, mirroring the era’s pervasive acknowledgment of death’s omnipresence. Such cultural artifacts illuminate the prevalent mindset regarding expectancy and mortality, underscoring the emotional and social influences that underpinned individuals’ attitudes toward lifespan.

A key element to consider when delving into life expectancy in the 1600s is the role of religion and spirituality, which permeated daily life and had profound implications on mortality. In a period rife with superstition and theological worldview, many communities attributed ailments to divine retribution or the will of higher powers. This belief system could often exacerbate health crises, as individuals might forgo traditional medicine or community assistance in favor of faith-based solutions. The implications were substantial; communities oftentimes experienced critical health crises, leading to fluctuations in population and life expectancy patterns that starkly deviated from more scientifically informed practices that would emerge in later centuries.

Regional discrepancies in life expectancy require dissection as well. In contrast to European nations, certain African tribes exhibited cultural practices deeply intertwined with their environment, impacting overall health. The use of traditional medicinal practices among indigenous populations played a multifaceted role in enhancing life expectancy. The symbiotic relationship with their environment allowed these communities to thrive in ways that traditional European practices could not always replicate, corroborating the importance of cultural practices on health outcomes.

One cannot overlook the transformative developments brought about by the advent of the Enlightenment, especially towards the latter half of the 1600s. This intellectual movement heralded a newfound emphasis on empirical observation and scientific inquiry, laying the groundwork for more accurate data collection on life expectancy. The shift towards valuing observation could lead to increased awareness of health practices, educating populations on hygiene, diet, and disease prevention. In retrospect, this emerging paradigm signaled a gradual move towards a more nuanced understanding of health that juxtaposed spiritual beliefs with rational thematization of bodily functions.

In synthesis, the 1600s were characterized by a complex interplay of variables that affected life expectancy. Cultural relativism provides an enriching framework to understand how individuals and societies navigated health, mortality, and existence amid varied influences. Through this lens, it becomes clear that life expectancy was not merely a demographic measure but a rich tapestry woven from the threads of culture, politics, and social conditions. Recognizing this multifaceted narrative prompts curiosity and open-mindedness towards historical populations and their unique challenges—reminding us that understanding human longevity invites contemplation on our own lives and the orientations we take towards health and mortality today.