When one contemplates the epoch of the cavemen, a mélange of images floods the mind: primitive tools, rudimentary shelters, and the all-pervading specter of survival against a harsh backdrop of nature. Yet, how long did these early humans inhabit the earth? The term “cavemen” evokes an anachronistic notion of prehistoric people who perhaps spent their entire existence confined within cave walls. However, to distill their essence and timeline into a simplistic narrative would be a gross oversimplification. What follows is an exploration of the duration of existence for these remarkable beings and a plunge into the depths of their lives through the prism of cultural relativism.

The timeline of human evolution is a complex tapestry interwoven with myriad threads of history. The genus Homo, to which modern humans belong, first emerged approximately 2.8 million years ago. Yet, the iconic image of Homo sapiens, or modern humans specifically referred to as ‘cavemen,’ illustrates a mere sliver of that vast expanse of time. Behavioral modernity, characterized by our species’ capacity for complex thought, symbolic behavior, and social structures, began to crystallize around 50,000 years ago. This period, often dubbed the Upper Paleolithic, witnessed the flourishing of art, advanced tool-making, and structured societal interaction.

This brings us to a critical inquiry: If cavemen existed for such a prolonged period, what intrinsic factors influenced their survival? The answer lies not solely within the realm of biology but rather in the rich tapestry of cultural evolution. As human beings were increasingly social creatures, cooperation became paramount. The development of language and shared cultural narratives allowed groups to devise strategies for survival, including hunting techniques, foraging, and even early forms of governance that transcended the mere struggle for resources.

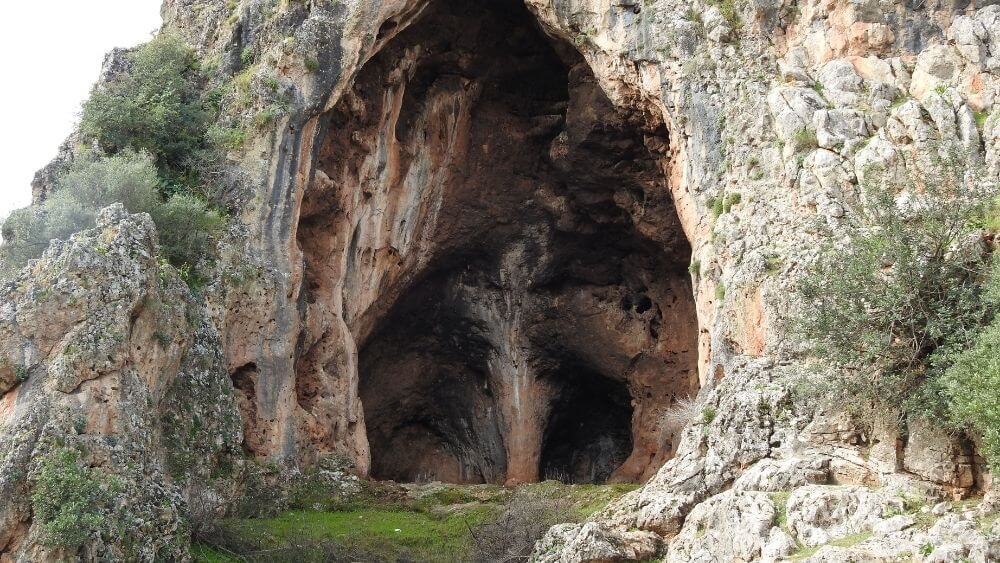

Among the most essential aspects of caveman life was, undoubtedly, their need to adapt to a myriad of environments. Archeological evidence suggests that early humans exhibited a remarkable degree of flexibility, permitting their dispersal across diverse terrains—from icy tundras to verdant forests. As cave dwellers, they took refuge in natural shelters, but the notion of living “in caves” is often misleading. Many prehistoric communities constructed temporary structures; caves served as supplemental shelters rather than permanent residences. In truth, these populations frequently oscillated between various habitats based on seasonal availability of resources, typically following herds of animals or migrating in search of edible vegetation.

The concept of cultural relativism invites an examination of the caveman lifestyle from an ethical standpoint, devoid of contemporary biases. The heuristic frameworks through which we construe prehistoric life can lead to misconstrued interpretations of their existence. Life for these early Homo sapiens was not merely about survival; it involved a rich interplay of cultural practices, social bonds, and communal knowledge. In essence, their existence was both a response to environmental challenges and a manifestation of evolving cultural paradigms.

Contrary to the romanticized portrayal of cavemen as brutish, savagery-driven beings, the archaeological record reveals a nuanced existence. Evidence of burial practices indicates a recognition of life beyond death. Engravings, paintings, and ceremonial artifacts found in various sites offer a glimpse into a world where symbolism and meaning were intricately woven into the social fabric. Thus, it is prudent to challenge the playful question: Were cavemen merely survivalists, or did they engage in a complex cultural dialogue over the span of their existence? The answer suggests a perplexing yet profound reality—a synthesis of both survival and cultural evolution.

As we aesthetically examine their tools, it becomes clear that cavemen were sophisticated engineers of their own survival. The development of crafted implements from stone, bone, and wood speaks volumes of their ingenuity and adaptive spirit. These artifacts, which evolved over millennia, reflect not only functional design but also signify the emergence of style and identity within social groups. The inception of regional styles hints at a burgeoning sense of belonging and differentiation that transcended mere utilitarian needs. This development inevitably invites much curiosity: Did the creation of art and tools signify a nascent self-awareness that prompted early humans to consider their place in the cosmos?

Moreover, the societal constructs of these ancient groups invite exploration of familial and social dynamics. They likely engaged in cooperative breeding practices that furthered not only genetic diversity but also fortified communal ties. The group dynamics were inherently reciprocal; thus, survival hinged on shared responsibilities, from food gathering to child-rearing. Cultural relativism posits that each grouping, based on environmental or experiential contexts, developed distinct social frameworks—thus facilitating varied adaptations to life’s challenges.

In scrutinizing the duration of existence for cavemen through the lens of cultural relativism, one encounters a breathtaking panorama where life was enmeshed in nature, society, and shared ideology. Thus, the inquiry into how long cavemen lived transcends mere chronological analysis; it demands a holistic investigation into the interconnectedness of survival, culture, and awareness. The advent of agriculture and the eventual dawn of recorded history signaled the phasing out of the traditional caveman lifestyle, yet, in their brief tenure, they lay the groundwork of human civilization that persists in varying forms today.

In conclusion, understanding the lives of cavemen is a sophisticated endeavor. Their existence was a tapestry woven with existential challenges and intricate cultural narratives, defying simplistic interpretations. The proverbial ‘brutal truth’ reveals a disparate yet rich life imbued with relationships, adaptability, and a quest for meaning—elements that resonate deeply in the complexity of human evolution. Thus, the prolonged existence of our caveman ancestors is not simply measured in years but rather in the indelible impact they had on humanity that, to this day, shapes our collective consciousness.