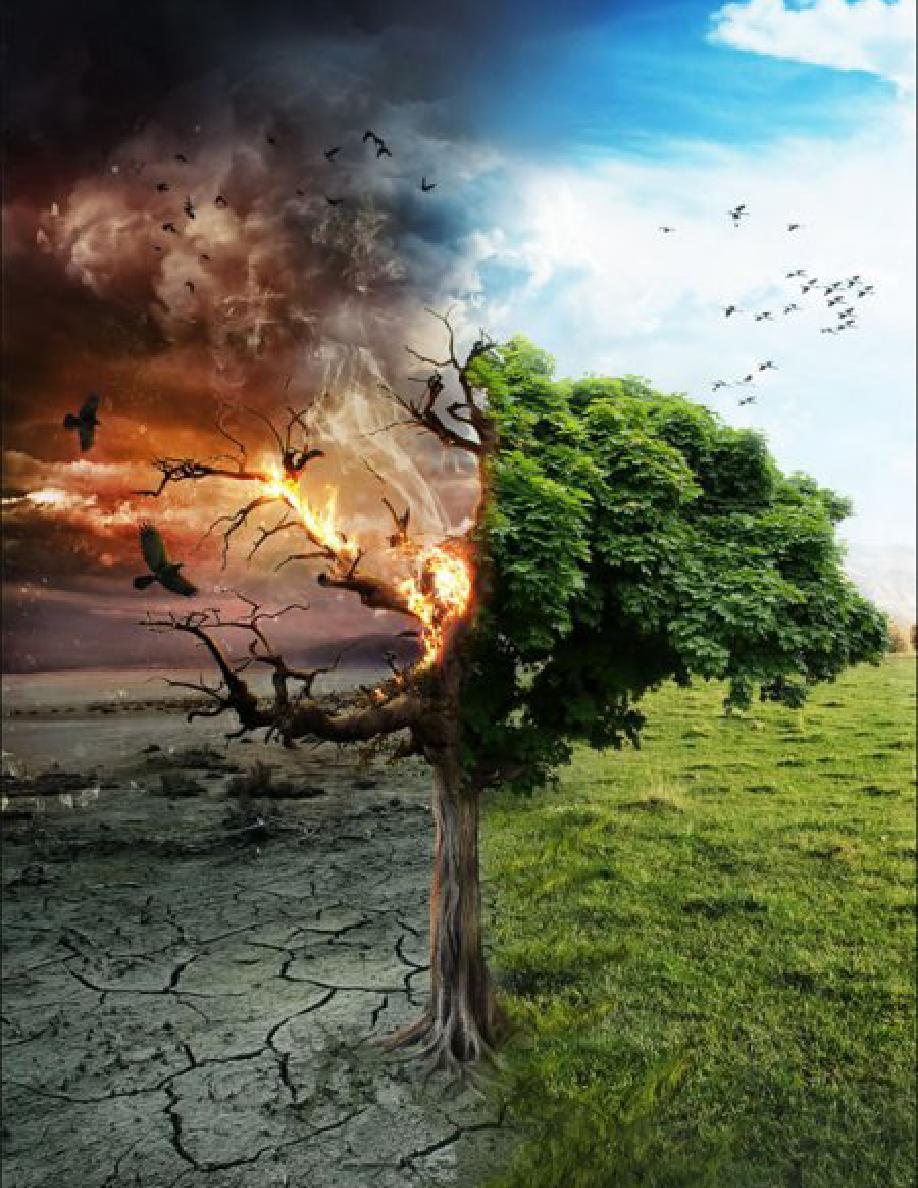

The proverb “A good tree cannot bear bad fruit” serves as a poignant aphorism, honing in on the intrinsic relationship between the quality of an entity and the outcomes it produces. This adage, often cited in both literary and rhetorical contexts, carries profound implications in various disciplines including ethics, psychology, and agriculture. Its essence lies not only in the literal interpretation concerning trees and fruit, but extends to individuals and their actions within societies. This article endeavors to elucidate the multifaceted nature of this proverb, while also exploring its implications in contemporary discourses.

Historically, the proverb has its roots in agrarian societies, where the health of a tree directly correlates with the quality of its fruit. A well-tended tree, nurtured with proper care and suitable conditions, yields fruit that is typically nutritious and palatable. Conversely, a tree that is diseased or neglected produces fruit that is often spoiled or unappealing. This dichotomy invites a broader analysis into the relationship between cultivation and the manifestation of quality in various forms.

Firstly, one can consider the proverb’s application within the framework of ethics. In moral philosophy, this adage serves as an influential metaphor illustrating the connection between an individual’s character and their actions. When a person is morally upright, their decisions tend to reflect that goodness, resulting in positive contributions to society. Conversely, an individual steeped in unethical behavior is likely to produce detrimental outcomes. This correlation invites discourse on the nature of morality and the potential for personal growth or redemption. It poses the question: can a person truly change for the better, thereby bearing ‘good fruit’ despite a history of ‘bad fruit’ production?

Moreover, this proverb extends to the institution of family and parenting. In familial units, the upbringing of children often serves as a microcosm of societal values. If a parent nurtures their offspring with love, respect, and moral guidance, the expectation is that the children will grow to exhibit similar virtues. Yet, historical anomalies can emerge where, against all odds, children diverge from their upbringing and develop into individuals who embody values opposite to those instilled in them. This dichotomy highlights the complexities of environment, genetics, and personal agency in the shaping of character.

The economic sphere also provides fertile ground for the proverb’s application. Businesses serve as modern analogues to trees, with their outputs (or ‘fruits’) representing the products, services, or legacies they create. A company that embraces ethical practices—such as fair labor, environmental stewardship, and corporate social responsibility—is likely to engender positive public perception and customer loyalty. Yet, firms embroiled in malfeasance or exploitation find themselves beset by disdain, as they yield ‘bad fruit’ in the form of tarnished reputations and legal repercussions. This dynamic not only affects the stakeholders immediately involved but ripples outward, impacting economies and communities at large.

A further dimension emerges when contemplating the proverb’s relevance to education. Educational institutions are designed to cultivate the minds of their students. The quality of education received is expected to yield knowledgeable, capable graduates—‘good fruit’ in the labor market and broader society. However, the debate endures on the merits of standardized testing and rote memorization as just measures of educational success. When a system fails to account for diverse learning styles or socio-economic barriers, the ‘fruit’ may become stunted or malformed, rendering the value of education questionable in certain contexts.

Interpersonally, the proverb can be examined through the lens of friendship and social circles. It posits that the quality of relationships is reflective of the character of the individuals within them. Genuine friendships are often established upon trust, loyalty, and shared values. However, associations built on convenience or mutual benefit can yield friendships that are superficial or toxic. These relationships, akin to ‘bad fruit,’ may ultimately bring hardship or dissatisfaction, prompting reflection on the qualities sought in personal connections.

Furthermore, the adage prompts an exploration of self-reflection and personal accountability. It invites individuals to examine their output—both in thought and action. The quest for self-improvement hinges upon recognizing the inherent qualities one embodies. Are one’s intentions pure? Do actions align with personal values? Such introspection compels individuals to strive for an alignment that fosters the production of ‘good fruit’—in essence, a legacy characterized by positive influence and integrity.

Finally, this proverb encourages a consideration of societal structures and collective behaviors. Communities that prioritize inclusivity, diversity, and support systems tend to flourish, producing citizenry that reflects those collective values. In contrast, communities marked by strife and division often yield societal outcomes that reflect their discord—prompting conversation about the nature of collective responsibility and momentum toward positive change.

In conclusion, the proverb “A good tree cannot bear bad fruit” is a rich tapestry of interpretations that resonate across multiple domains. Whether in ethical discussions, familial dynamics, economic discourse, educational paradigms, interpersоnal relationships, or societal structures, the essence of the proverb remains salient. It compels individuals and collectives alike to engage in introspection and accountability, fostering an environment where flourishing outcomes can be anticipated. Ultimately, the pursuit of cultivating ‘good trees’ can yield fruits that not only enhance personal lives but contribute positively to the fabric of society as a whole.