In the lexicon of contemporary discourse surrounding race and ethnicity, the terms “Caucasian” and “White” ignite fervent debate. These terms, seemingly interchangeable, are far from synonymous, veiling a complex interplay of historical, cultural, and social nuances. To navigate this intricate landscape, one must unearth the etymological origins, sociocultural implications, and the very essence of identity dictated by these terms.

First, it is imperative to trace the etymology of “Caucasian.” This term emerged in the late 18th century, coined by the German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. His classification was ostensibly scientific, premised on cranial measurements and purported racial hierarchies, assigning Caucasians to a supposed pinnacle of human development. Blumenbach derived the term from the Caucasus region, claiming it as the locus of the most “beautiful” skulls. This notion inadvertently fostered the myth that beauty and racial superiority were inherent to this demographic.

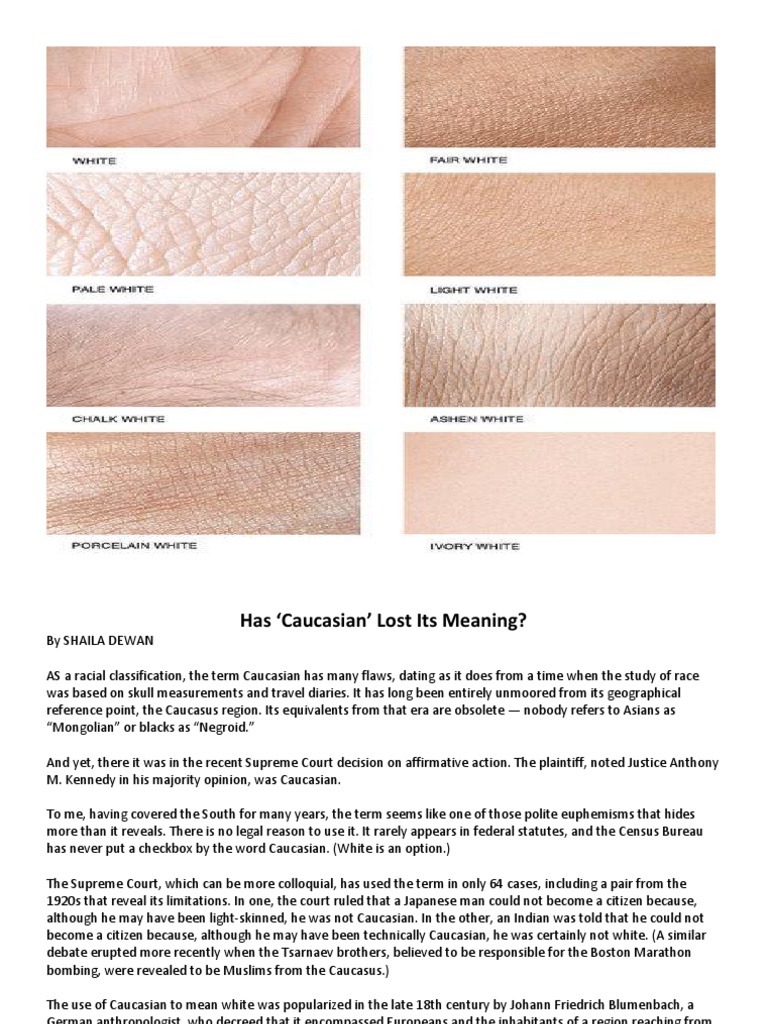

In contrast, the term “White” is a broader and more nebulous category, encapsulating individuals of European descent, and extending sometimes to those from the Middle East and North Africa. Unlike “Caucasian,” the label “White” often carries sociopolitical connotations fused with privilege and power dynamics. The pedestrian use of “White” transcends academic lineage; it is entrenched in the societal fabric of Western civilization, implicating layers of historical context, including colonialism and systemic inequality.

With the emergence of modernity, the term “Caucasian” has evolved within the conversation surrounding racial identity. In contemporary discourse, it may encompass a range of identities, often aimed at emphasizing a unifying racial identity associated with European descent. However, this generalization can effectively erase distinctions that are crucial within the arena of cultural relativism. Such reductions overlook individual histories, experiences, and identities, reducing multifaceted human existence to an oversimplified binary.

The distinction between “Caucasian” and “White” also unveils a complex web of privilege and positionality. Within the United States, the concept of Whiteness has engendered a societal structure that privileges certain groups over others. This hierarchy can obscure the experiences of those who, although classified as “White” or “Caucasian,” do not share in the privileges accorded to the dominant narrative of Whiteness. It becomes essential to recognize that these terms are not merely descriptors but rather, they are laden with historical burdens and expectations.

To unravel this conundrum further, one must examine the implications of these identities amidst emerging discourses on intersectionality. The understanding of race is increasingly contextual rather than universal, affected by variables such as class, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity. For instance, Caucasian individuals from economically disadvantaged backgrounds may experience discrimination and marginalization that transcends racial identity. Thus, employing either term without a careful consideration of context runs the risk of perpetuating stereotypes and myths that sustain systemic discrimination.

Moreover, the usage of “Caucasian” or “White” has transcended scientific classification to become social identifiers in various settings, often informing personal relationships and professional dynamics. Colloquially, asking whether someone is “Caucasian” may elicit different responses than inquiring if they identify as “White.” The former implies adherence to a racial taxonomy long discredited by contemporary anthropology, while the latter encapsulates broader social and political dimensions that cannot be easily parsed without a deep-seated acknowledgment of their historical baggage.

In recent years, a growing body of academic literature calls into question not only the accuracy but the very viability of these racial classifications. With the advent of genetic science, the idea of race has increasingly been challenged. Biologists affirm that genetic variation within so-called races is significantly greater than that between them—inviting one to reconsider these categorizations in light of scientific

understanding. Consequently, to label individuals strictly as “Caucasian” or “White” is to indulge in a reductive practice that fails to grasp the biocultural complexities of humanity.

An intriguing metaphor to encapsulate this discourse might be a kaleidoscope—vibrant and multifaceted, each turn shifts perspectives and reveals new configurations. Just as the patterns in a kaleidoscope are intricate yet unified by a common vessel, identities represented by “Caucasian” and “White” are multifarious, reflecting unique intersections that color individual experiences. The notion of racial identity can be simultaneously clear and contradictory, highlighting vulnerabilities while illuminating common threads that bind disparate histories.

In sum, while “Caucasian” and “White” may appear as mere descriptors within the societal lexicon, their implications are profound and layered. To address the complicated relationship between these terms necessitates a commitment to cultural relativism, recognizing that humanity cannot be distilled into binary classifications without sacrificing the unique complexity of individual identities. The conversation surrounding these terms should evolve, reflecting an understanding that promotes inclusivity and rejects monolithic representations. Moving forward, the challenge remains for society to foster dialogues that honor this complexity, paving a path toward a more equitable understanding of race and ethnicity in a rapidly changing world.