The anatomy of human teeth has long been a subject of fascination and debate among anthropologists, dental scientists, and nutritionists alike. Central to this discourse is the question: are human teeth anatomically and functionally designed for a carnivorous diet? This inquiry delves deeply into a wider consideration of human evolutionary biology, dietary adaptation, and cultural relativism. The premise involves an exploration of the anatomical characteristics of human dentition against the backdrop of historical dietary practices, revealing a nuanced understanding of how these factors coexist within the framework of human culture.

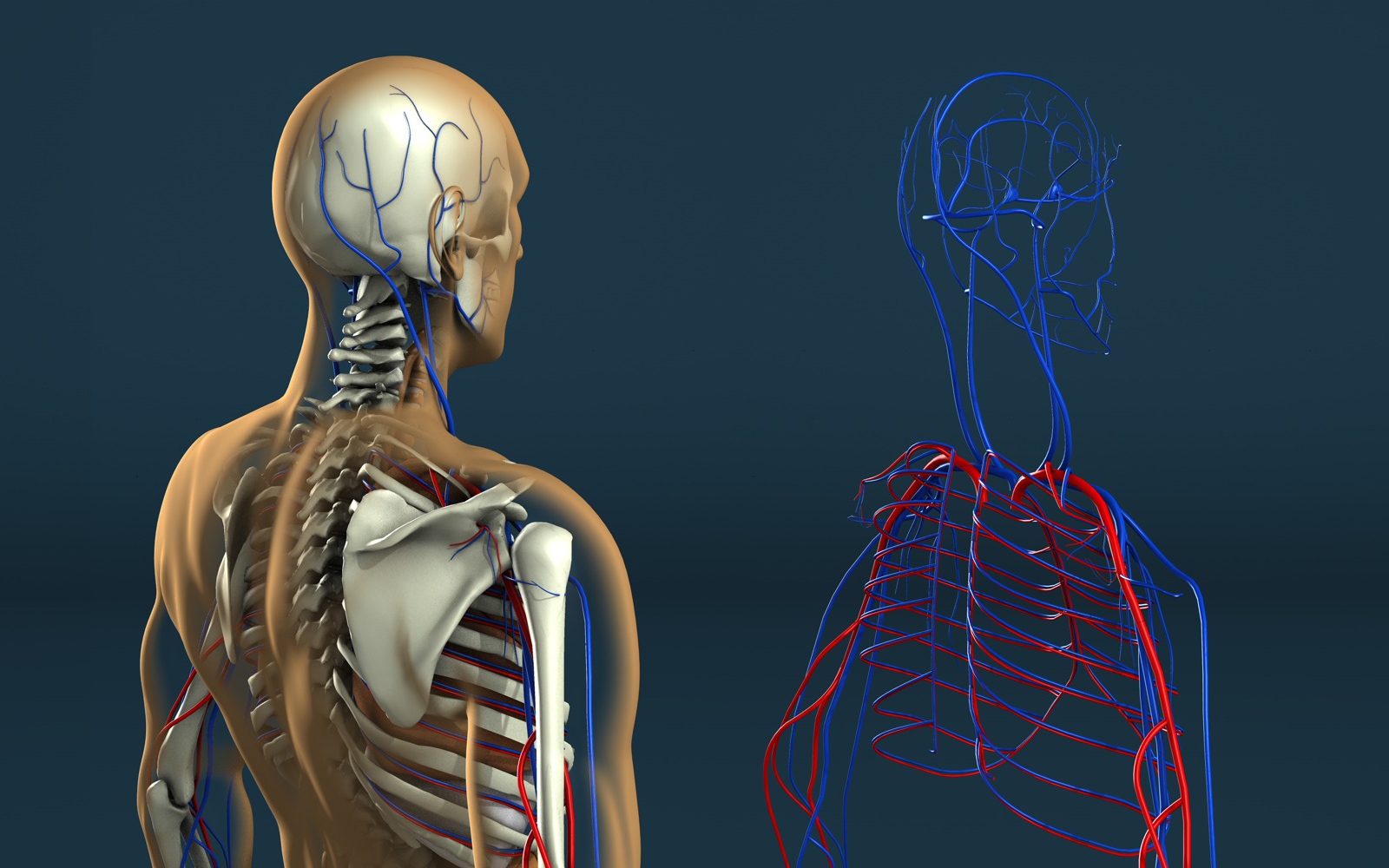

To embark on this examination, it is imperative to first understand the construction of human teeth. Human dentition typically consists of four types of teeth: incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Incisors are flat and ideal for cutting, canines are pointed and serve to tear, while molars are broad, enabling grinding and chewing. This differentiation speaks to an omnivorous diet, equipped to handle a variety of food sources, including fruits, vegetables, grains, and meat. However, the question remains: how did these dental structures evolve in relation to the dominant dietary practices throughout human history?

The evolutionary journey of hominins offers valuable insights. Early human ancestors, such as Australopithecus, exhibited dental traits that reflected a predominantly herbivorous diet, which was characterized by robust molars suitable for grinding fibrous plant material. The shift towards more varied dietary sources emerged with the emergence of the genus Homo. Evidence suggests that Homo habilis and later Homo erectus began utilizing tools to process food, allowing for an increase in meat consumption. This transition is not merely a consequence of anatomical adaptation; it is also a reflection of sociocultural developments that occurred alongside hunting practices and the eventual domestication of animals.

The cultural relativity of diet cannot be understated. Different societies have developed unique culinary practices that reflect their geographical, environmental, and social circumstances. In some cultures, meat forms a central component of the diet, while in others, plant-based foods reign supreme. The dietary customs can influence tooth wear and dental health, further supporting the argument against a unidimensional view of human dentition as being solely designed for meat consumption. For instance, populations that predominantly consume starch-rich diets often present with distinct dental wear patterns when compared to those that regularly incorporate meat.

The morphological characteristics of teeth must also be considered through the lens of biomechanical efficiency. The structure of human teeth allows for versatile use. A biological trait beneficial for a meat-based diet might also provide advantages for omnivorous habits. This adaptability serves as a testament to the resilient and opportunistic nature of human beings, allowing for the assimilation of various food sources. It is crucial to note that modern dental morphology has been influenced not solely by evolutionary necessities but also by nutritional availability and cultural preferences.

Furthermore, the role of cooking and food preparation ought to be contemplated. The advent of cooking, which can be traced back roughly 1.5 million years, facilitated the breakdown of food, making nutrients more bioavailable and reducing the dietary demands on teeth. Species that consumed raw meat or fibrous plants required a more robust dental structure; however, with the transition to cooked food, there emerged a symbiotic relationship between human biology and cultural technology. Thus, the design of teeth adapted not just to diet but also to the methodologies employed therein.

In the modern context, contemporary dietary habits present a perplexing challenge. The delineation of human teeth as either designed for meat or plant matter is convoluted by processed foods rich in sugar and carbohydrate content. Such diets can lead to a plethora of dental issues, including caries, gum disease, and premature tooth loss. The misguided notion that our teeth are predominantly built for meat consumption fails to account for the damage inflicted by neglecting preventive dental care in the face of modern eating practices.

Cultural perspectives on diet also engender discussions surrounding ethical considerations and sustainability. As societies increasingly grapple with the implications of meat consumption, including environmental impact and animal rights, the narrative continues to evolve. Some communities advocate for plant-based diets, positing these practices as not only healthier but ethically superior. In this light, the historical interpretation of human dentition becomes more complex. It demands an appreciation of not just the physical attributes of teeth but also the larger sociocultural movements that shape perceptions of food and health.

To conclude, the assertion that human teeth are solely designed to eat meat is inadequate when contextualized within the rich tapestry of human evolution, diet, and culture. Human dentition embodies the adaptability and cognitive evolution of the species, reflecting a varied dietary journey influenced by both biological and cultural determinants. Continued exploration of this topic fosters a greater understanding of how humans navigate dietary choices and informs broader discussions about health, nutrition, and ethical consumption in our contemporary milieu.