Throughout human history, milk has held a complex position within various cultures, serving not only as a nutritional sustenance but also as an emblem of sociocultural identity. In examining whether humans are biologically predisposed to consume milk, one must consider the intricate interplay between dietary habits, evolutionary biology, and cultural relativism. This article delves into the perspectives of nutritionists regarding human milk consumption, informed by diverse cultural practices and biological adaptations.

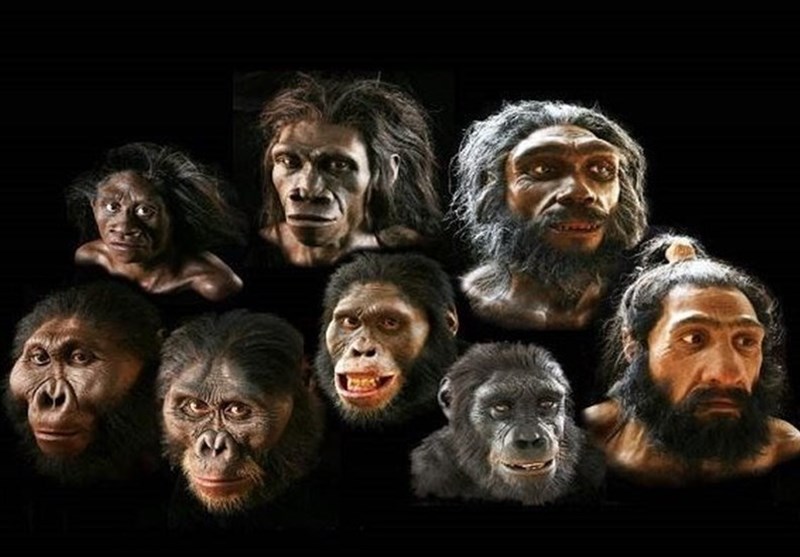

To begin with, it is essential to unpack the biological perspective. Humans are unique among mammals in that a significant portion of the adult population can digest lactose, the sugar found in milk. This ability, known as lactase persistence, evolved in response to the domestication of dairy animals. In regions where dairying became prevalent, such as Northern Europe and parts of Africa, genetic mutations facilitated sustained production of lactase—an enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose. This evolutionary adaptation illustrates that certain populations have developed a tolerance for milk consumption, laying the foundation for milk’s role in their diet.

Conversely, many populations, particularly in Asia and parts of South America, lack this genetic mutation and, consequently, experience lactose intolerance. This biological reality challenges the notion that drinking milk is universally beneficial or suitable for all humans. As such, the prevalence of lactose intolerance underscores the importance of examining the cultural context behind dietary practices, as well as the notion of “normalcy” associated with milk consumption.

Nutritionally, milk is esteemed for its content of calcium, vitamin D, and protein, which are vital for bone health and overall physiological functions. Nutritionists frequently advocate for the inclusion of milk and dairy products in the diet for those who can consume them without adverse effects. However, during recent years, a shift has been observed in dietary recommendations. Some experts argue for the diversification of calcium sources, promoting a broader array of nutrient-rich foods as alternatives to dairy. This shift highlights a growing awareness that nutrition is not a one-size-fits-all prescription but rather a spectrum that varies based on individual health needs, preferences, and cultural backgrounds.

In cultures where dairy is a staple, milk is imbued with profound significance beyond its nutritional value. Within Scandinavian cultures, for instance, fermented dairy products like yogurt and kefir are integral to traditional diets, reflecting centuries of culinary practices. These practices emphasize communal ties and heritage, illustrating how food is intertwined with identity. On the other hand, cultures that traditionally eschew milk often alternate forms of sustenance that fulfill similar nutritional roles, such as legumes, nuts, and leafy greens. Such variations emphasize the adaptability of human diets in response to available resources and cultural preferences.

Contemporary health discussions have also prompted scrutiny of dairy consumption from ethical and environmental perspectives. The rise of veganism and plant-based diets has encouraged individuals to reconsider their consumption of animal products, including milk. Proponents of plant-based diets argue that environments shaped by modern agricultural practices can harm ecosystems and animal welfare. This ethical stance dovetails with cultural relativism, as individuals navigate and define health and sustainability through their own cultural lenses.

Another dimension to consider in this dialogue is the marketing and commercialization of milk and dairy products. The dairy industry, particularly in Western countries, has historically positioned milk as a fundamental food group, with campaigns emphasizing its supposed health benefits. This societal perception can impose a sense of obligation upon individuals to consume milk, thereby creating a sociocultural expectancy. As the tide of wellness trends continues to surface, particularly within social media landscapes, individuals may find themselves grappling with conflicting messages about food and health. Hence, the cultural narrative surrounding milk becomes deeply enmeshed within broader discussions on health, identity, and sustainability.

As perspectives evolve, so too have dietary patterns. In contemporary societies, many individuals are turning towards non-dairy milk alternatives, including almond, soy, and oat milk. These products cater to diverse dietary needs and preferences, presenting exciting new avenues for nutrition. Nevertheless, the nutritional content of these alternatives varies widely, and individuals must remain discerning consumers to ensure they meet their dietary requirements. In essence, the proliferation of non-dairy options provides an opportunity to challenge traditional dietary norms and invites critical interrogation of long-standing beliefs regarding milk consumption.

In synthesizing the various dimensions of milk consumption, it becomes evident that the question of whether humans are supposed to drink milk cannot be answered in absolutes. Rather, it encompasses a rich tapestry of biological, nutritional, cultural, and ethical considerations. The human experience with milk exemplifies the broader principle of cultural relativism, urging us to recognize the profound influence of societal practices, environmental factors, and individual choices on dietary habits. By embracing this complexity, we can appreciate the diverse roles that milk, and by extension food, play in shaping human culture and health.

Ultimately, choosing whether to consume milk or seek alternatives rests within the hands of individuals, informed not only by personal preferences but also by the intricate web of cultural values and nutritional science. This blend of individual agency and cultural influence reflects humanity’s ongoing evolution, demonstrating that our relationship with food remains as dynamic as the societies we inhabit.