Emotional expression often heralds the complexities of human experience, as intricate as the interweaving threads of a tapestry. Among the most poignant manifestations of emotion is crying, a behavior traditionally associated with humans. This behavior transcends mere biological necessity and beckons a broader inquiry: Are humans indeed the only animals that cry? To unravel this conundrum, one must adopt a cultural relativism perspective, thereby appreciating the myriad ways that different species articulate their feelings.

Crying, in its essence, signifies an emotional outpouring—an involuntary response to stimuli that invoke sorrow, frustration, or even joy. Within human constructs, it assumes various forms, from tears of grief to those born of laughter. The act serves not only as a personal release but also as a social signal, inviting empathy from onlookers. It composes a narrative that proliferates through shared experience. Yet, the inquiry into animal emotions and expressions invites a divergence from the anthropocentric viewpoint that has long overshadowed this domain.

Numerous studies suggest that certain non-human animals exhibit behaviors that mirror human crying, albeit under different circumstances or for various reasons. Elephants, for instance, are known to produce vocalizations characterized as crying in response to loss or distress within their social groups. This behavior emphasizes a profound emotional architecture, highlighting a capacity for grief that parallels the human experience.

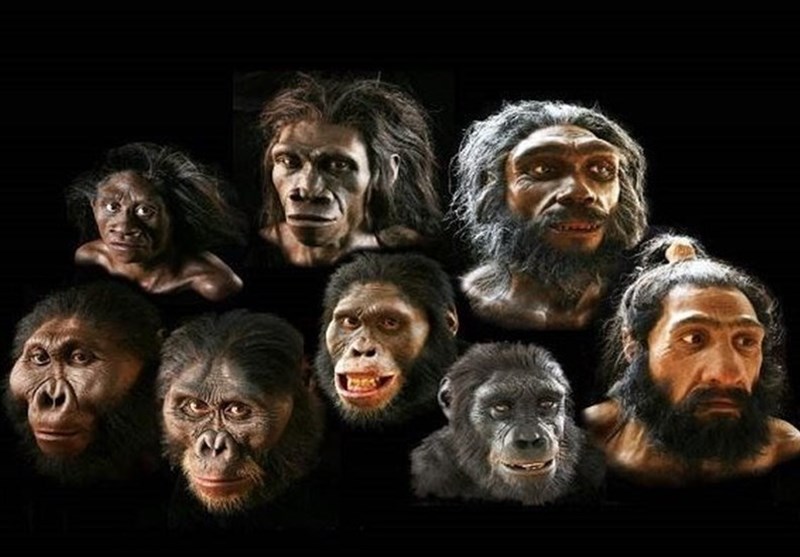

Moreover, primates such as chimpanzees and gorillas manifest tearful responses, particularly under conditions of profound emotional stress. Research has documented instances where these sentient beings shed tears during moments of separation or trauma, underscoring similarities in emotional processing. Such examples prompt an ethical reevaluation of the uniqueness of human emotional expression, stirring a foundational question: is the delineation between human and animal emotions as stark as society has maintained?

The cultural relativism perspective advocates for the understanding that emotional responses are not monolithic. They are shaped by social structures, environmental contexts, and evolutionary histories, which differ dramatically across species. This approach fosters a critical examination of why crying is delineated as an exclusively human phenomenon, a designation arguably steeped in Western narratives that privilege emotional experiences influenced by cultural contexts.

In exploring the concept further, one must consider the role of neurological frameworks in the emotional lives of various species. Investigations into the limbic system—the brain’s emotional core—reveal parallels across species, suggesting that many mammals possess the neural architecture necessary for emotional expression. This observation challenges the declarative assertion that only humans can cry, pushing the dialogue into a nuanced realm of interdisciplinary research encompassing psychology, ethology, and cultural studies.

Nevertheless, the act of crying is imbued with cultural significances variably interpreted across disparate human societies. Consider, for example, the juxtaposition of Western cultures, where crying is frequently stigmatized in public settings, against others where it is embraced as a natural and necessary expression of vulnerability. These cultural narratives shape not only the individual’s experience but also societal norms surrounding acceptable emotional expression. This serves to highlight an essential tenet of cultural relativism: emotional expressions, including crying, are contingent on socio-cultural interpretations.

Additionally, the methodology employed in studying animal emotions is critical. Anthropomorphism—the attribution of human traits to non-human entities—can distort interpretations of animal behaviors. Researchers navigating these waters must strike a delicate balance between scientific rigor and empathetic understanding. The lens through which animal emotions are perceived can either diminish or enrich the value of their experiences, thus impacting the broader discourse on emotional expression.

Furthermore, the investigation into crying among various animal species confronts us with compelling ethical considerations. If animals can indeed express emotions akin to grief, happiness, or distress, the implications for conservation and animal welfare are significant. Awareness of these emotional capacities emerges as a moral imperative, urging societal advocates to reconsider not only how animals are treated but also how their emotional worlds are validated within the tapestry of life.

Transcending beyond a mere exploration of who cries and who does not, the dialogue encapsulates a holistic understanding of emotional expression—a narrative woven with threads of empathy across species. The metaphor of the universal tapestry of feelings, interlaced with human experiences and animal behaviors, beckons a richer exploration of tears and emotional release.

In conclusion, the question “Are humans the only animals that cry?” veers toward a complex and layered inquiry. The answer hinges not simply on biological mechanisms but also on the vastly divergent cultural narratives that define emotional expression. Therefore, while humans uniquely articulate a wide spectrum of emotions through tears, the broader investigation reveals that other species may indeed share an empathic resonance, blurring the lines once thought immutable. The emotional lives of animals, much like our own, speak to an enduring interconnectedness, a vivid, pulsating reminder of the shared fabric of existence across life forms. As such, it is imperative that society embraces a pluralistic view of emotional expression, one that celebrates the multifaceted ways love, loss, and joy can manifest in this world we share.