Are humans the only sentient beings on this planet? This question, whimsical yet profound, has beguiled thinkers for millennia. The inquiry invokes layers of philosophical debate and scientific investigation, compelling us to ponder not only our own existential status but also that of other life forms. In traversing this contentious terrain, we enter into the realms of cultural relativism, a perspective that urges us to interpret experiences through varied cultural lenses. This discussion synthesizes philosophical theories, scientific perspectives, and the implications of cultural relativism, seeking to unravel the enigma of sentience.

To embark on this exploration, we first define sentience. Sentience typically refers to the capacity to experience feelings, sensations, and consciousness. Philosophers have long wrestled with the implications of sentience — who possesses it and to what extent. René Descartes famously opined that animals lacked rationality and therefore, by extension, sentience. This Cartesian dualism formed a tidy dichotomy, where humans occupied the realm of reason, relegating animals to mere automata. However, over the centuries, this view has been progressively challenged.

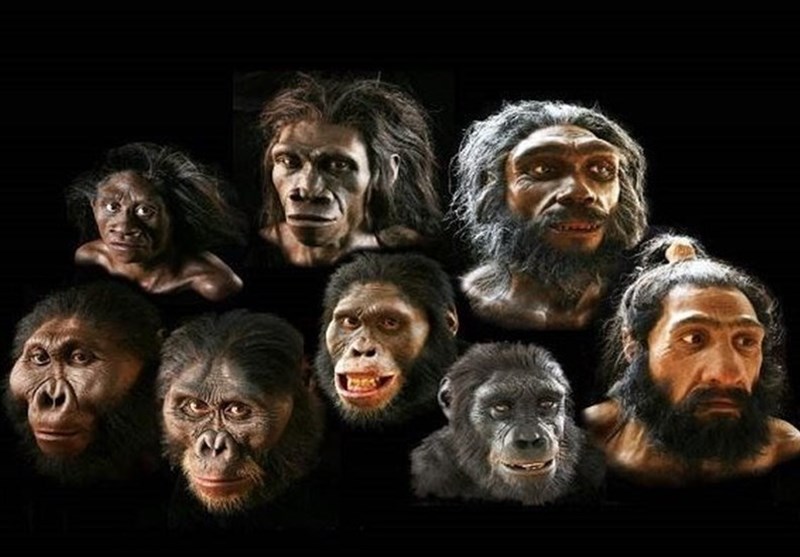

The advent of ethology and cognitive ethology has significantly reshaped our understanding of animal cognition. Researchers such as Jane Goodall have documented behaviors in primates that suggest self-awareness and emotional complexity, casting doubt on the traditional boundary between humans and other species. The ability of elephants to display emotional responses to loss, or dolphins to demonstrate sophisticated communication skills, urges us to reevaluate our conception of sentience. Are we, in our cultural arrogance, overly inclined to deem other beings as lesser simply because we inhabit a different evolutionary niche?

Cultural relativism plays a pivotal role in this discussion by reminding us that our understanding of sentience is inextricably linked to our cultural narratives and experiences. Different cultures have various interpretations of what it means to be sentient. In many indigenous cultures, for instance, animals are regarded as fellow beings with whom humans share the earth, infusing them with spiritual significance. This contrasts sharply with the utilitarian view prevalent in modern Western societies, where non-human animals are often perceived as resources to be exploited. Such divergent perspectives compel us to entertain the notion that our definitions of sentience may not be universally applicable.

Furthermore, the anthropocentric lens often employed in scientific inquiry can hinder our ability to appreciate the complexity of non-human intelligence. Language, a hallmark of human identity, has been historically viewed as a threshold for sentience. Yet, there are myriad forms of communication within the animal kingdom that defy our narrow parameters. The intricate dances of bees, the songs of birds, and the complex social structures of ants reveal systems of communication that serve functional purposes akin to language. These behaviors prompt a reevaluation of how we gauge sentience, fostering an understanding that transcends human-centric criteria.

Philosophers such as Peter Singer have further advanced the discourse on sentience through the lens of utilitarian ethics, positing that the ability to suffer or experience pleasure is a critical determinant of moral consideration. This perspective raises the question of whether our ethical frameworks should extend beyond humans to encompass all sentient beings, regardless of species. Singer’s arguments evoke a sense of moral urgency, compelling us to confront the ethical implications of our treatment of animals. If we acknowledge that non-human beings can experience suffering, does this not obligate us to reconsider our practices?

The challenge posed by the inquiry into sentience is not solely theoretical but also practical. As modern science continues to unravel the complexities of animal cognition, it becomes imperative for us to assimilate this knowledge into our ethical frameworks and cultural narratives. For instance, the growing field of animal consciousness studies is revealing profound insights into the cognitive capabilities of various species, urging legislation that protects the welfare of sentient beings. In response, some cultures and societies have already begun to shift their ethical paradigms, adopting animal rights legislation and promoting vegetarianism or veganism as ethical choices.

As the scientific community continues to disclose startling discoveries regarding animal intelligence, the implications for human consciousness are equally profound. The boundary separating us from other creatures may not be as rigid as previously thought. This realization compels us to grapple with our hubris and engage in a collective contemplation of our role within the broader tapestry of life. This invites a playful yet poignant challenge: if sentience is not wholly encapsulated by the human experience, what does this mean for our own identity? Are we merely a species among many, or do we retain a unique mantle of sentience that establishes our dominion?

In summation, the question of whether humans are the only sentient beings propels us into a broader dialogue on consciousness, ethics, and interspecies relations. Cultural relativism serves as a vital lens through which we can better understand the nuances of sentience, acknowledging that our perceptions are molded by the very societies we inhabit. The philosophical debates surrounding this topic encourage us to transcend our species-centric viewpoint, revealing a more complex and interconnected web of life. As we stand on the precipice of an evolving narrative, the dance between science and philosophy continues, eliciting new questions while reconciling the age-old dichotomy of man versus nature. Ultimately, the maze of sentient existence remains a field ripe for exploration, laden with implications that stretch far beyond our individual species.