The phenomenon of lactose intolerance presents a compelling anthropological narrative that encompasses genetics, cultural adaptation, and dietary evolution. This article seeks to explore whether the majority of humans are indeed lactose intolerant, and what the broader implications of this condition are within the framework of cultural relativism. Through a comprehensive examination of lactose digestion, its evolutionary trajectory, and the interplay between biology and culture, we can gain deeper insights into human dietary practices and preferences.

To begin, it is essential to understand the biological underpinnings of lactose intolerance. Lactose is the sugar found in milk and dairy products, and its digestion relies on an enzyme known as lactase. In most mammals, including humans, lactase production diminishes after weaning, leading to an inability to properly digest lactose. This decline results in the symptoms associated with lactose intolerance: bloating, gas, diarrhea, and abdominal pain after the consumption of dairy products.

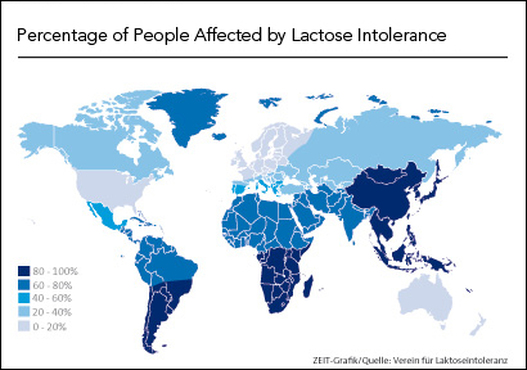

Globally, lactose intolerance varies significantly across populations. Some estimates suggest that approximately 68% of the world’s population exhibits some degree of lactose malabsorption, with prevalence rates soaring to upwards of 90% in certain ethnic groups, particularly among East Asian, African, and Indigenous American populations. In stark contrast, many Northern European groups have developed lactase persistence, a genetic adaptation that allows continued lactase production throughout adulthood. This genetic variation reveals much about the interplay between environment, diet, and human adaptability.

The evolution of lactase persistence is a remarkable example of gene-culture coevolution. In pastoralist societies where dairy farming became prevalent, individuals who retained their ability to digest lactose had a nutritional advantage. With dairy serving as a rich source of calories and hydration, such adaptation facilitated survival and reproductive success, leading to the propagation of lactase persistence in these populations. Conversely, cultures that did not adopt dairy farming did not experience the same selective pressures, resulting in higher rates of lactose intolerance.

From a cultural relativism perspective, the significance of lactose intolerance extends far beyond mere biological responses. In cultures where dairy is historically absent from the diet, individuals may view lactose intolerance not as a deficiency but as a normative aspect of their identity. This cultural lens allows for a more nuanced understanding of lactose intolerance as a spectrum rather than a dichotomy of normal and abnormal. To contextualize lactose intolerance, it is imperative to consider the cultural frameworks within which food choices are made and the meanings ascribed to those choices.

The fascination with dairy consumption is inextricably tied to its historical and socio-cultural relevance. In many Western cultures, dairy products have become emblematic of health and nourishment, often associated with essential nutrients such as calcium and vitamins. Campaigns promoting dairy consumption have further entrenched these ideas, neglecting the realities of those who cannot tolerate it. This cultural narrative raises ethical questions about food equity and access to dietary alternatives for those who experience lactose intolerance.

In regions where lactose intolerance is prevalent, traditional dietary practices often make accommodations for this condition. Fermented dairy products such as yogurt and cheese, for instance, have lower lactose content and are thus more digestible. These adaptations illuminate a form of cultural resilience, where societies have innovated culinary practices to harmonize traditional food sources with physiological needs. Such advancements underscore the relationship between cultural practices and biological realities, demonstrating how human adaptability is not solely confined to genetic evolution but also encompasses cultural modifications.

The interplay between dietary habits and cultural identifiers cannot be overstated. For many non-dairy-consuming cultures, the avoidance of lactose-rich foods is culturally embedded. This adherence is frequently reinforced through social practices, familial traditions, and communal meals, fostering a sense of belonging and continuity. Lactose intolerance, therefore, emerges not merely as an individual health concern but as a shared community attribute, influencing collective dietary norms and practices.

Furthermore, the modern globalized world poses new challenges to these traditional practices. As global markets expand, there is an influx of dairy products into regions historically devoid of such foods. This transition often leads to dietary shifts that can have profound implications for health and well-being. Increasingly, lactose intolerance becomes a topic of discussion not only among individuals but also within the wider public health discourse. Addressing lactose intolerance in these varied cultural contexts necessitates sensitivity and respect for indigenous dietary customs while also advocating for informed choices among diverse populations.

In conclusion, whether the majority of humans are lactose intolerant cannot be distilled into a simple affirmative or negative answer; rather, it reflects a complex tapestry woven from threads of biology, culture, and history. The evolutionary narrative of lactose digestion illustrates human adaptability in response to environmental pressures, while cultural relativism expands our understanding of dietary practices and preferences. Ultimately, the conversation surrounding lactose intolerance compels us to rethink our approach to food, embracing a more inclusive perspective that acknowledges the rich diversity of human experiences and dietary habits. As we navigate this complex landscape, it becomes evident that food is not merely sustenance; it embodies the very essence of cultural identity, survival, and adaptation.