Throughout history, humanity has grappled with the alterations of climate, yet the concept of an “Ice Age” tends to evoke stark images of glaciers engulfing continents and the survival of primitive peoples. In reality, we find ourselves amidst complex climate cycles, making the question of whether we are currently living in an Ice Age both provocative and multifaceted. This discussion hinges not merely on scientific facts but also on cultural relativism—how different societies interpret and engage with climate phenomena. The ensuing exploration will elucidate the dimensions of our contemporary climate within the context of Earth’s climatic history and its cultural ramifications.

To begin with, it is important to understand the classification of Ice Ages. The term “Ice Age” refers to prolonged periods in Earth’s history characterized by the expansion of ice sheets and glaciers, influenced by a plethora of factors such as orbital variations, atmospheric composition, and tectonic activities. Presently, we inhabit what is known as the Quaternary Ice Age, initiated approximately 2.58 million years ago, marked by cycles of glacial and interglacial periods. This brings us to the current epoch, the Holocene, which is generally regarded as an interglacial period. Thus, while we reside in an Ice Age, we are not enduring the chilling conditions typically associated with this term.

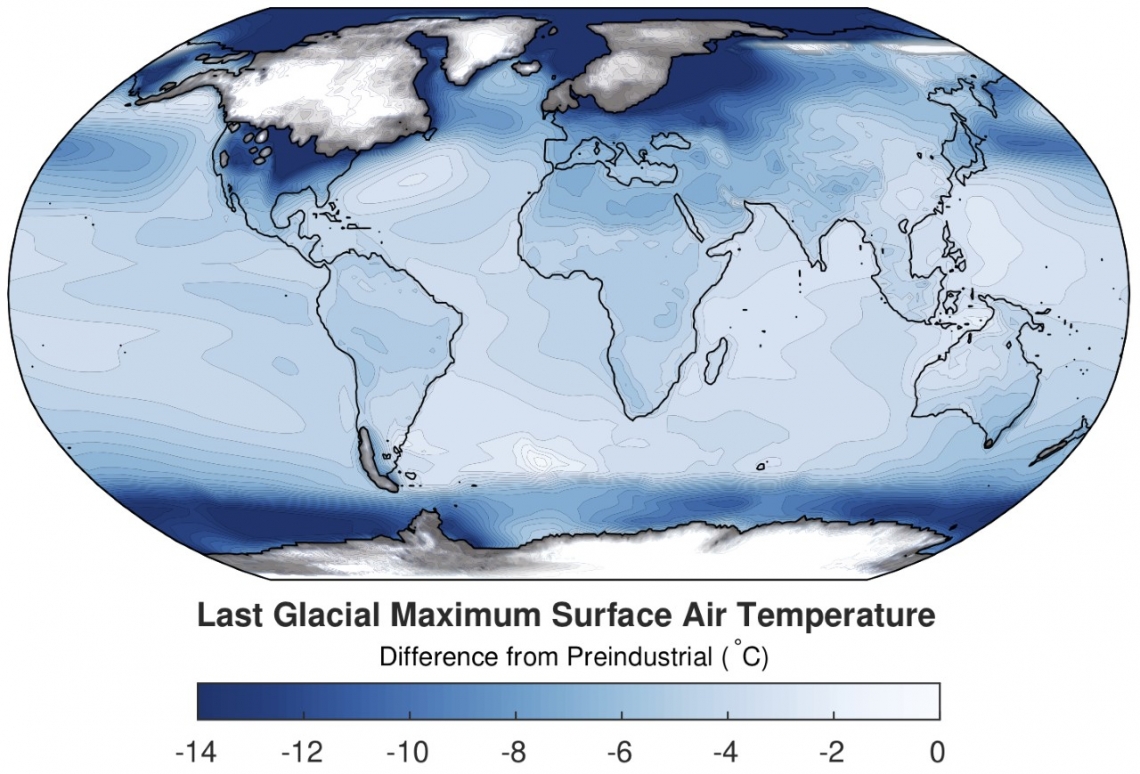

The Earth’s climate operates on intricate cycles. Milankovitch cycles, a theory founded by Serbian astrophysicist Milutin Milanković, encapsulates the variations in Earth’s movements—eccentricity, axial tilt, and precession—that produce climate changes over millennia. As these cycles ebb and flow, they lead to differing lengths of glacial and interglacial periods, with glacial epochs portraying drastic cooling phases. For instance, the last glacial maximum occurred approximately 20,000 years ago, wherein vast portions of the Northern Hemisphere were shrouded in ice. In contrast, present climatic conditions reflect a substantial interglacial phase, raising questions about how different cultures interpret and respond to these climate realities.

In examining climate from a cultural relativism perspective, it is imperative to recognize that ecosystems frame human experiences, even shaping the very paradigms through which societies interpret their environmental realities. For example, indigenous communities in Arctic regions maintain extensive cultural and spiritual connections to their landscapes, perceiving their environment through traditional ecological knowledge, which has been accumulated over generations. They possess an understanding of climate patterns that informs their hunting, gathering, and overall livelihood. Contrastingly, industrialized societies often view climate phenomena through a lens of immediacy, primarily concerned with their environmental impact and adaptation strategies. This dichotomy presents a rich tapestry of interpretations encompassing our multifaceted climate experiences.

Climate cycles also dramatically influence cultural narratives, emphasizing the importance of narrative in constructing collective identities. The Norse sagas, chronicling the lives of Scandinavian settlers, illustrate an acute awareness of their environment and its vicissitudes. The Viking Age was punctuated by warmer periods enabling exploration and colonization, while the subsequent Little Ice Age brought hardship and depopulation. Conversely, contemporary narratives often revolve around the impending catastrophes predicted by climate scientists. Cultural depictions of climate change, such as in film and literature, frequently evoke dystopian futures, which may galvanize social action or engender fatalism within populations.

Moreover, examining climate change through a cultural lens reveals that perceptions of time can differ substantially across cultures. Western cultures typically adopt a linear perspective, where time progresses towards a defined future. This perspective often fuels anxiety regarding climate change, and in turn, spurs scientific and technological innovations aimed at mitigation. In contrast, many indigenous cultures embrace a cyclical understanding of time, wherein the past, present, and future are interconnected. This worldview fosters resilience and adaptability, focusing on harmony with nature rather than antagonism.

Interestingly, contemporary scientific research substantiates the cyclical nature of climate; however, the speed and magnitude of current changes invoke a sense of urgency absent in previous cycles. The anthropogenic contributions to climate change, predominantly through the release of greenhouse gases, pose unprecedented challenges. Herein lies a critical juncture, as societal response to climate phenomena is largely dictated by cultural frameworks. Some cultures may feel empowered to innovate new agricultural practices or renewable technologies, while others may resort to traditional methods in a bid to maintain equilibrium with disrupted ecosystems.

Furthermore, the discourse surrounding climate justice reveals inherent cultural disparities. Minority communities often bear the brunt of climate impacts despite contributing least to its causation. These intersections of class, race, and geographical location render climate cycles not purely scientific issues but complex social dynamics as well. Addressing such disparities necessitates an inclusive approach in climate discourse that recognizes and respects diverse cultural perspectives.

Ultimately, as we consider whether we are living in an Ice Age, it becomes clear that the answer transcends mere scientific inquiry; it involves a thorough exploration of how varied cultures engage with and interpret climatic shifts. Bringing together scientific understanding and cultural perceptions fosters a more holistic comprehension of our current epoch, wherein our responses can be informed by both empirical data and the rich tapestry of human cultural experience. Hence, engaging in dialogues about climate systems and their implications can enhance our collective capacity to navigate the intricacies of both our environmental and sociocultural landscapes.