Human skin color is an intricate tapestry woven by evolutionary biology, environmental adaptation, and cultural interpretations. The question of whether white people represent a genetic mutation invites profound inquiry into the complexities of human variation, evolutionary history, and sociocultural implications. As we navigate this multifaceted discourse, it is essential to disentangle the scientific facts from the myths typically entrenched in societal narratives.

To embark on this inquiry, one must first understand that human skin color arises from a combination of genetics, environmental factors, and adaptation mechanisms. Melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color, plays a pivotal role in determining one’s hue. Evolutionarily, variations of skin tone have been shaped by geographical location and exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR). For instance, populations residing in equatorial regions with intense solar radiation tend to have darker skin, which offers protective benefits against UVR’s deleterious effects. Conversely, those in northern latitudes, where sunlight is limited, evolved lighter skin to facilitate vitamin D synthesis in conditions of lower UV exposure.

However, labeling a particular skin color as a “mutation” necessitates careful consideration of the terminology at play. The term “mutation” often connotes a deviation from a so-called norm, typically implying a negative connotation. In contrast, the lighter pigmentation characteristic of many white individuals should be understood as a unique adaptation to specific environmental stimuli rather than a deviation. Thus, while lighter skin may be the result of genetic adaptations to particular ecological niches, it is not indicative of a malfunction or a mistake in the human genome.

From a cultural relativism perspective, the interpretation of skin color has evolved significantly across different societies and historical contexts. Historically, numerous cultures have ascribed various meanings to skin color, often assigning social status, beauty standards, and racial hierarchies derived from ethnocentric views. In the Western paradigm, especially during the colonial and post-colonial eras, a hierarchical classification was established wherein lighter skin was often associated with superiority, status, and desirability. This social construct has ramifications that extend into contemporary discussions regarding race, privilege, and systemic inequities.

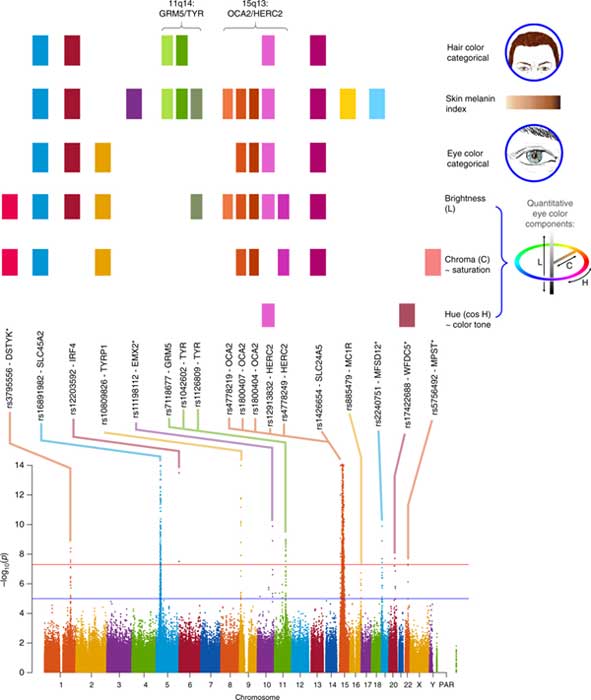

To delve deeper, one must consider the gene variants associated with skin color. Research has identified key genes, such as SLC24A5, ASIP, and TYR, that contribute to variations in pigmentation. For example, the SLC24A5 gene, commonly found in Europeans, is believed to be a significant factor in lighter skin pigmentation. The spread of these genetic traits through interbreeding and migration events further illustrates the fluidity of skin color as a trait and its susceptibility to environmental pressures.

When framed through the lens of cultural relativism, it becomes evident that viewing skin color as a mere scientific phenomenon overlooks the sociocultural dimensions that inform individual and group identities. The notion of race, which primarily categorizes individuals based on physical characteristics, lacks a biological basis but carries substantial social weight. It is this dichotomy that fuels ongoing discussions about identity, privilege, and the collective experiences of marginalized communities.

Furthermore, it is crucial to interrogate the sociohistorical narratives that accompany skin color. The association of lighter skin with superiority has perpetuated an enduring legacy of racism and discrimination. Interestingly, demographic shifts driven by globalization and migration have begun to challenge traditional notions of race, presenting opportunities for a more nuanced understanding of identity. As societies become more multicultural, perceptions of skin color will continue to morph, ushering in a shift towards greater acceptance and inclusivity.

However, the inquiry into whether white individuals are genetically “mutated” must address the broader implications of such claims. The reframing of white skin as a variant adaptation should not overshadow the enduring impact of colonialism and its aftereffects. Historical misuse of biological determinism to justify injustices and inequalities necessitates sensitivity in these conversations. Engaging with the rich tapestry of human history and the confluence of genetics and culture is paramount in transcending binary thinking regarding race and identity.

In conclusion, while the scientific inquiry into skin color highlights the adaptive nature of human biology, it also exposes the complexities underlying racial categorizations. Lighter skin, rather than representing a genetic deviation, is an illustration of human adaptability to environmental cues. The interplay between genetics and culture in shaping paradigms of identity and race continues to evolve, prompting vital discussions around privilege and social justice. A more comprehensive understanding of skin color through the lens of cultural relativism invites us to recognize the inherent value in human diversity. It challenges us to reevaluate preconceived notions of race and to advocate for a society that values inclusivity and equity, fostering a milieu that celebrates the richness of human life in all its forms.