The average lifespan in Ancient Egypt presents a captivating blend of reality and the profound cultural intricacies that underpinned this ancient civilization. Through a lens of cultural relativism, one can explore the multifaceted dimensions of life, health, and the afterlife, offering keen insights into how these aspects shaped the Egyptian worldview. This exploration not only highlights the empirical data regarding lifespan but also evokes deeper inquiries into the societal values, medical practices, and spiritual beliefs that defined this historical epoch.

The average lifespan of individuals in Ancient Egypt is often estimated to be around 30 to 40 years. However, this figure is somewhat misleading, as it does not represent the full story of health and longevity in this society. Mortality rates, particularly among infants and children, contributed significantly to this average, severely skewing perceptions of lifespan. Child mortality was exceptionally high, with many infants succumbing to diseases and nutritional deficiencies. It was not uncommon for families to experience the loss of multiple children before reaching adulthood. Thus, those who survived into their twenties or thirties often led lives extending well into their fifties or sixties. Such a discrepancy invites a more thorough examination of the cultural significance ascribed to life’s fragility in Ancient Egypt.

This societal emphasis on the afterlife is another critical dimension that warrants scrutiny. The Egyptians’ belief in an eternal existence beyond the grave fundamentally shaped their perception of life. Knowledge of the afterlife infused daily existence with spiritual significance, creating a culture markedly distinct from contemporary understandings of health and mortality. The Egyptians conceived of a duality: the physical and the spiritual. The corporeal body was considered a temporary vessel, while the soul, or ‘Ka’, was believed to continue its journey in the afterlife. This dualistic philosophy fostered a unique approach to health and wellness, emphasizing the harmony of body and spirit.

Moreover, the medical practices of Ancient Egypt reflect a sophisticated understanding of health, intermingled with their spiritual beliefs. Physicians in this civilization were held in high regard, engaging in a mix of empirical knowledge and religious healing rituals. They utilized medicinal plants, surgical techniques, and various therapeutic practices that indicate an advanced level of medical knowledge for their time. The Edwin Smith Papyrus and the Ebers Papyrus stand as testaments to their medical sophistication, revealing an array of treatments for ailments ranging from simple injuries to complex diseases. Healing, however, was often intertwined with spells and invocations, illustrating the belief that one’s physical ailments were sometimes manifestations of spiritual discord.

The role of diet and nutrition also played a pivotal part in influencing health and lifespan among the ancient Egyptians. Their diet was predominantly plant-based, consisting of grains, vegetables, and fruits. The consumption of bread, beer, and legumes formed the backbone of their daily sustenance. However, the nutritional value varied significantly between social classes, with the elite enjoying a more diverse diet that included meats, fish, and dairy products. Malnutrition was prevalent among the lower classes, limiting their physical robustness and resilience against disease. This discrepancy, accentuated by socioeconomic status, highlights integral facets of cultural relativism, demonstrating how societal structures directly influenced health outcomes and overall longevity.

Understanding Ancient Egyptian attitudes toward death and the afterlife elucidates their cultural relativism. The grandiose pyramids and elaborate tombs constructed for pharaohs signify a civilization that placed extraordinary importance on burial practices. For the Egyptians, death was not the end; rather, it was a transition into another realm of existence. They believed that a proper burial ensured the deceased’s safe passage to the afterlife, enabling individuals to maintain their identities beyond the physical realm. Rituals, such as mummification and the inclusion of grave goods, underscore the elaborate measures taken to prepare for this transition. These practices reflect a deeply embedded cultural narrative that instilled purpose and reverence in the act of dying, contrasting sharply with more contemporary views on mortality.

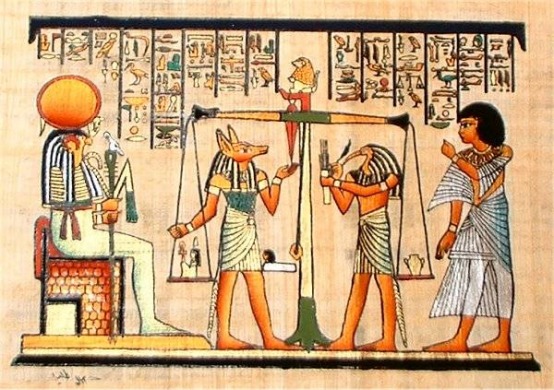

Furthermore, the journey to the afterlife was perceived as a trial that involved the weighing of the heart against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. This metaphorical weighing serves as a moral compass, encouraging individuals to live virtuously and honorably, thereby affecting attitudes toward life and health. The emphasis on morality as a determinant of one’s fate in the afterlife led Egyptians to adopt health practices that extended beyond mere physical wellbeing. They viewed ethical living and social responsibility as essential facets of a life well lived, reinforcing the interconnectedness between individual health and societal harmony.

In conclusion, the average lifespan in Ancient Egypt transcends mere numerical representation, inviting an intricate discourse on the cultural philosophies that shaped their understanding of life, health, and the afterlife. The interplay of high infant mortality, advanced medical practices, dietary habits, and the influential belief in an eternal afterlife collectively fostered a rich tapestry of meaning regarding existence. Applying a cultural relativism perspective unveils critical insights into how the ancient Egyptians navigated the complexities of mortality, embracing both the ephemeral nature of life and the profound potential of continued existence beyond death. This multifaceted exploration underscores the profound fascination with Ancient Egypt, revealing not only the data regarding lifespan but the cultural narratives that resonate through time.