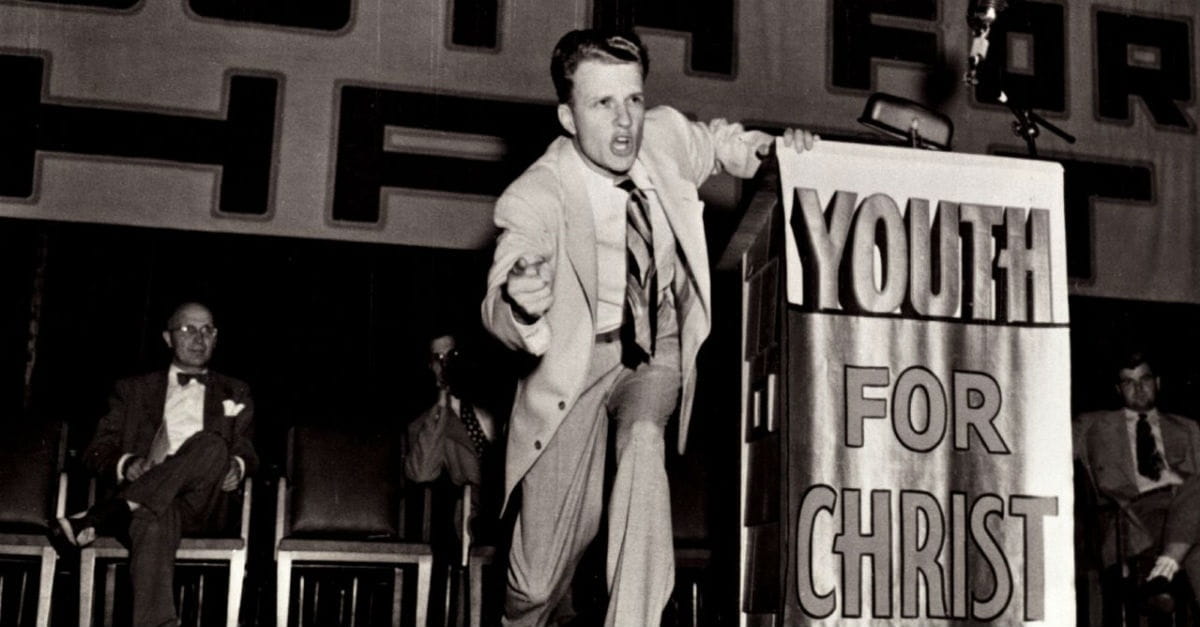

Billy Graham, an eminent figure in American evangelicalism, became a pivotal ally during the Civil Rights Movement, transcending cultural barriers through his steadfast commitment to justice, equality, and faith. The intermingling of these ideals presents a compelling basis for examining how religion can act as a catalyst for social change, particularly through the lens of cultural relativism. As we delve deeper, a nuanced understanding of Graham’s contributions and the broader implications of his work emerges, prompting us to reconsider the role of faith in the ever-evolving landscape of social justice.

To comprehend the impact of Graham on the Civil Rights Movement, one must first contextualize the era’s prevailing attitudes toward race and justice. The mid-20th century was characterized by deep-seated racial tensions, with segregation and discrimination systematically permeating the societal fabric. In contrast, the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement sought to dismantle these oppressive structures, advocating for the inherent dignity and equal rights of all individuals, irrespective of their race. Graham’s involvement was not merely a political standpoint but rather a profound manifestation of his theological convictions.

Graham’s theological framework provides insight into his engagement with social justice issues. Rooted in evangelical Christianity, his belief in the equal worth of every individual was not just aspirational but scriptural. The biblical principle that all humans are created in the image of God underpinned his stance against racial inequality. This belief system became a powerful motivational force, enabling him to rally diverse audiences, transcending the confines of cultural and racial distinctions. Graham’s calls for racial integration during his crusades were not simply motivated by public relations concerns, but by a deeply ingrained conviction that faith must inform practice in a way that promotes justice.

In the analysis of Graham’s role in the Civil Rights Movement, one must consider quintessential moments that shaped his trajectory. For instance, during a 1953 crusade in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Graham famously insisted that the venue be desegregated. His refusal to allow racial segregation within his audience underscored a radical shift in perspective for a leading evangelist at the time. This decision was not without controversy; yet, it positioned Graham as a figure willing to confront the status quo, thus challenging the cultural norms that prevailed within both religious and societal contexts.

Furthermore, Graham maintained friendships and collaborations with prominent civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. This alliance was emblematic of a broader movement within the evangelical community that was beginning to grapple with issues of race and justice. Graham’s unwavering support for King and the movement’s cause illustrated a convergence of faith and activism that was groundbreaking for his followers. By elevating the discourse around these troubling social issues, Graham helped catalyze a transformative reconsideration of what it meant to practice faith in a context fraught with injustice.

Examining Graham’s impact through a cultural relativism perspective reveals the complexity of faith in relationship to societal change. Cultural relativism posits that one’s beliefs and practices must be understood within their societal context rather than evaluated against external standards. Graham’s theological assertions were influenced by the cultural milieu of mid-20th century America, yet they also played a role in altering that very context. In advocating for equal rights, Graham sought to elevate the moral foundations of society, thereby inviting others to engage in a collective effort toward racial reconciliation.

Interestingly, the conversations surrounding Graham’s contributions often intersect with criticisms regarding the evangelical community’s historical complicity in systemic racism. Acknowledging these uncomfortable truths is essential for a holistic analysis of Graham’s legacy. While his function as an ally for civil rights was noteworthy, one must also interrogate the broader evangelical movement’s response to racial injustices both past and present. A critical lens allows for an assessment of how Graham’s individual acts of defiance against segregation might juxtapose against a community that has, at times, resisted confronting its own shortcomings.

In a further exploration of the implications of Graham’s activism, one encounters the challenge of reconciling faith with the exigencies of social justice. The concept of faith as an actionable force implies that believers must engage not just in personal devotion but also in communal activism. The duality of Graham’s message—that faith leads to action—propels discussions about the responsibilities of religious leaders today. A contemporary audience can glean valuable lessons from Graham’s example, perceiving the intersection of faith and justice not as divergent paths but as interconnected avenues leading toward collective flourishing.

As the discourse shifts towards the future of social justice within faith communities, Graham’s contributions offer a critical foundation for understanding the interplay between belief systems and societal transformation. Promulgating the notion that faith is not static but dynamic, Graham’s legacy can inspire a contemporary theology that actively seeks dismantling both personal and communal barriers to equity. In this vein, we are encouraged to reflect upon our own responsibilities as stewards of justice in a world fraught with disparities.

In conclusion, Billy Graham’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement exemplifies a transformative fusion of faith and justice. Through cultural relativism, one can appreciate how his faith expressed itself in activism, serving both as a reflection of societal values and a prophetic challenge to them. By revisiting Graham’s efforts, not only do we honor a historical figure, but we also engage with the pertinent question of how faith communities can, and must, engage with justice in our own times. It invites a keen inquiry into our own beliefs and actions as we navigate the complexities of an ever-changing societal landscape.