The postpartum period is a transformative phase in a woman’s life, marked by significant physical and emotional changes. One of the most common concerns among new mothers is the observation of bright red blood two weeks after childbirth. Understanding whether this phenomenon is normal or indicative of a potential complication is paramount, both from a medical standpoint and through the lens of cultural relativism. This exploration examines the intersection of physiological changes and cultural perceptions, providing insights into when such bleeding should raise alarms and when it can be deemed a natural aspect of the postpartum experience.

In an anthropological context, it is critical to first acknowledge that the postpartum experience varies widely across different cultures. In many societies, childbirth and its aftermath are enveloped in specific rituals and beliefs that influence perceptions of health and well-being. The presence of bright red blood, often interpreted as a sign of potent vitality or life force, may carry different connotations depending on cultural backgrounds. For instance, some cultures might view lochia—postpartum vaginal discharge—as an essential cleansing or purging process, an integral component of the transition to motherhood.

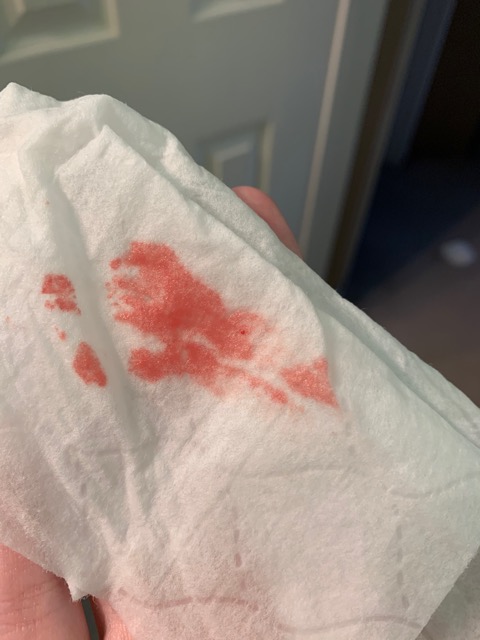

Lochia exists in three distinct stages: lochia rubra, lochia serosa, and lochia alba. Lochia rubra, which occurs within the first three to five days postpartum, consists predominantly of bright red blood. It is composed of blood, mucus, and uterine tissue, representing the body’s way of healing after the detachment of the placenta. However, by the second week postpartum, lochia is expected to transition to a pinkish hue as healing progresses. Yet, the persistence of bright red blood beyond this timeframe often triggers concerns about potential complications.

From a medical perspective, bright red blood that occurs two weeks postpartum may signal several different issues. Among these is the possibility of retained placental fragments, which can incite further bleeding and pose serious risks if not addressed promptly. The cultural implications of such complications can be profound, with some societies attributing postpartum hemorrhage to spiritual or supernatural factors. In certain cultures, women may seek traditional healers to address both the physical and metaphysical aspects of their condition.

Another potential cause of continued bright red bleeding is uterine atony, a condition where the uterus fails to contract effectively after childbirth. This may be particularly alarming in cultures that emphasize the importance of a woman’s ability to manage childbirth and postpartum recovery autonomously. Experiences of failure in this regard can lead to feelings of shame or inadequacy. Thus, understanding these cultural sentiments is vital when discussing postpartum complications and their implications for new mothers.

On the other hand, it is imperative to recognize that some degree of bright red bleeding can be entirely normal during the postpartum period. Many health professionals advise mothers not to fret unless the bleeding is accompanied by severe pain, large clots, or a foul odor, as these signs might indicate an underlying issue requiring medical attention. In many cultures, the process of childbirth and recovery is a communal experience, with family and friends providing emotional support and practical advice. This communal reinforcement can help alleviate fears surrounding normal physiological changes, including bleeding.

Moreover, cultural narratives surrounding motherhood play a significant role in shaping perceptions of the postpartum experience. In some societies, narratives may promote endurance and resilience, framing any signs of distress, including excessive bleeding, as a test of character. This can lead women to endure symptoms in silence rather than seek medical assistance, underscoring the intersection of gender norms and health practices. The tendency to minimize or overlook symptoms aligns with cultural constructs that valorize suffering in the pursuit of motherhood.

Conversely, there is a growing recognition of the importance of maternal health globally, leading to an increased emphasis on education and awareness regarding postpartum complications. In many modern societies, dialogues surrounding childbirth have shifted toward a more informed and proactive approach. Cultural relativism allows for the examination of how these shifts impact individual narratives and communal perceptions of postpartum bleeding and recovery. By integrating traditional knowledge with evidence-based medicine, communities can cultivate a more comprehensive understanding of these experiences.

In conclusion, the observation of bright red blood two weeks postpartum serves as a multifaceted concern that transcends mere medical assessment. It embodies a rich tapestry of cultural beliefs, personal expectations, and physiological realities. Within this context, the understanding of when to worry and when to dismiss bleeding as a normal aspect of recovery becomes nuanced. As health professionals and communities continue to navigate the complexities of postpartum care, a culturally informed approach—one that respects traditional practices while incorporating medical expertise—will foster better outcomes for mothers and their families.

Ultimately, the postpartum journey, fraught with both challenges and triumphs, is profoundly influenced by cultural contexts. Recognizing this interplay not only deepens our understanding of maternal health but also invites empathy and support for women as they navigate the uncharted territories of motherhood in diverse cultural landscapes.