Carbon dating, or radiocarbon dating, is a well-established method for determining the age of organic materials by measuring the decay of carbon-14 isotopes. However, when the discussion shifts to carbon dating rocks, a common question arises: Can we indeed carbon date rocks? The answer is a nuanced “no,” although the topic is rich with implications that extend into the realms of both geology and cultural relativism. Understanding the limitations of carbon dating necessitates an exploration into the broader methods of geological dating, the scientific principles involved, and the anthropological perspectives that shape our interpretations of these findings.

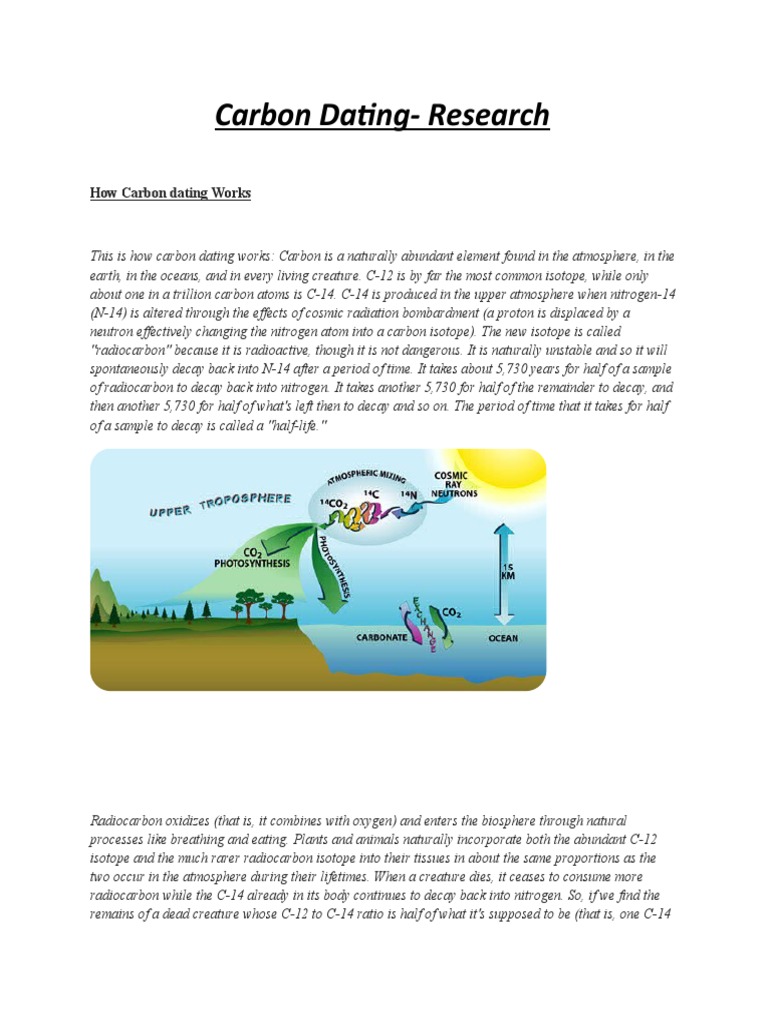

To embark on this exploration, one must first grasp the fundamental principles of radiocarbon dating. This technique is effective for dating materials that were once part of a biosphere—living organisms that incorporated carbon from the atmosphere or their environment. When these organisms die, the uptake of carbon halts, and the carbon-14 present begins to decay at a known rate, allowing scientists to estimate the time elapsed since the organism’s death. This process is undeniably robust, but rocks present a different challenge.

Rocks, particularly those formed from inorganic processes, do not contain carbon-14 in significant amounts. Instead, the age of rocks is typically determined through stratigraphy, radiometric dating of isotopes like uranium-lead or potassium-argon, and relative dating techniques. Each method has its own principles and limitations, underscoring the complexity of geological time scales and the significance of temporal context in understanding Earth’s history.

Ironically, the very act of dating geological formations offers a fascinating parallel to cultural perspectives on time itself. Different societies have distinct notions of historical narrative and the linearity or circularity of time. The scientific endeavor to ascertain the age of rocks—whether through the initial formation of the Earth, the evolution of various geological layers, or the extinction events that punctuate its history—can reflect back to how cultures codify their own historical experiences. In many indigenous cultures, time is perceived more cyclically than linearly, situating humanity within an ongoing narrative that interweaves with the environment.

In the context of cultural relativism, it becomes essential to address how scientific methods, such as geological dating, may clash or resonate with indigenous ontologies. For instance, some cultures may hold sacred understandings of rock formations, attributing spiritual significance and historical narratives to these natural structures. The geological time scales provided by scientists can conflict with the narratives held by these communities, prompting a deeper inquiry into the values embedded in our understanding of history and knowledge. Such clashes necessitate an academic rigor that respects local perspectives while engaging with scientific findings.

This discourse invites a deeper inspection of geological dating methods themselves. For example, uranium-lead dating can be applied to igneous rocks, utilizing the decay of uranium isotopes to assess age, while potassium-argon dating reveals insights into volcanic rock formations. These methods allow us to piece together the geological history of our planet across billions of years. Yet, they remain confined within the parameters of modern scientific frameworks, potentially sidelining thousands of years of indigenous knowledge about the earth’s formations.

The fascinating aspect of geological dating is not limited to the techniques employed; it also involves the ways in which our culture perceives those dates. In contemporary society, there often exists a gap between the scientific understanding of time and the socio-cultural narratives that pare our perception of history. This disjunction invites a broader conversation about how periods of geological time—measured in millions and billions of years—find resonance or dissonance in human-centric narratives.

Such contrasts prompt essential questions: How do we synthesize our understanding of a rock’s age through radiometric dating with the stories and meanings that rock holds for different cultures? How do we enrich a collective understanding of geological history while respecting the diverse narratives surrounding these natural elements? Ultimately, these considerations enhance the discourse surrounding both carbon dating and broader geological dating techniques.

To further enrich the conversation, scientists and anthropologists alike increasingly emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary approaches. By collaborating with indigenous communities and historians, scientists may develop methodologies that honor both empirical evidence and cultural significance. It becomes critical to foster dialogues where traditional ecological knowledge and scientific perspectives coalesce, allowing for a more comprehensive grasp of geological history that respects the tapestry of human experience.

In conclusion, while carbon dating is inapplicable to rocks, the examination of geological dating unveils layers of complexity intertwined with cultural narratives. In parallel, this exploration emphasizes the richness of interdisciplinary discourse. As we navigate the intricate relationship between scientific inquiry and cultural relativism, we may come to appreciate not just the age of rocks, but also the profound stories that both science and tradition reveal about our planet and humanity’s place within it. This synthesis fosters a more inclusive understanding of our shared past, helping to bridge the divide between empirical findings and the wisdom of ancestral knowledge.