Carbon dating and radioactive dating are two pivotal scientific methods employed in the chronometric assessment of ancient artifacts, geological layers, and archaeological findings. Each technique uses different isotopes and principles of radioactive decay to ascertain the age of materials, but they serve as vital tools in navigating the vast timeline of human culture and history.

Carbon dating, or radiocarbon dating, specifically targets organic materials. It quantifies the decay of carbon-14 (¹⁴C), a radioactive isotope present in the atmosphere. When an organism dies, it ceases to absorb carbon, leading to a gradual decay of ¹⁴C at a predictable rate, commonly expressed as half-life—approximately 5,730 years. This allows scientists to date organic remains up to about 50,000 years, providing insight into past cultures and environments.

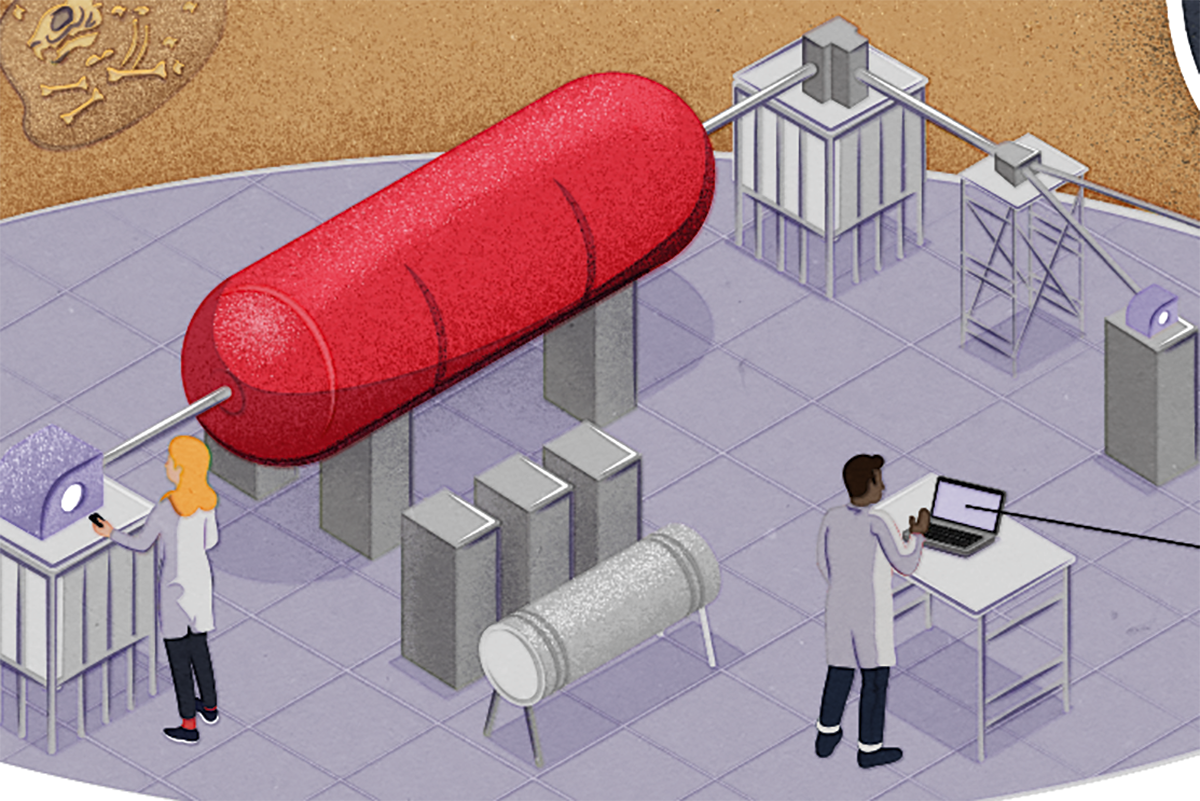

On the other hand, radioactive dating encompasses a broader spectrum of techniques. It employs various isotopes, not limited to carbon, to date both organic and inorganic materials. Potassium-argon dating, uranium-lead dating, and rubidium-strontium dating are prominent examples within this methodology, each possessing unique half-lives and ranges ideal for different contexts. For instance, potassium-argon is useful in dating volcanic rocks and ash, thus situating human civilizations within the broader geological timeline.

The persisting fascination with these dating methods emerges, in part, from humanity’s intrinsic desire to understand its own past. As cultures evolve, the narratives surrounding a civilization’s origin, development, and eventual decline become essential to collective identity. The ability to juxtapose tangible evidence against historical accounts enriches not only our comprehension of past societies but also informs contemporary social constructs. Indeed, the quest for precise measurement of time reflects a deeper cultural preoccupation with legacy and the ephemeral nature of existence.

From a cultural relativism perspective, perceptions of time and historical significance can differ markedly across societies. In some cultures, linear time is emphasized, whereby history is viewed as a straight continuum of events leading to the present. This view resonates with the carbon dating methodology, which anchors humanity within a quantifiable framework operating on a recognizable timeline. In contrast, other cultures may perceive time cyclically, wherein the past is constantly revisited and reinterpreted through rituals and oral histories. Such perspectives challenge the simplistic narratives imposed by linear models of history and invite nuanced interpretations of archaeological findings.

The contrasting frameworks of carbon dating and radioactive dating thus reflect deeper cultural values concerning temporality and significance. For instance, archaeologists working within cultures that embrace cyclic perceptions of time may approach the artifacts differently—acknowledging their relevance in ongoing narratives rather than merely as remnants of a linear past. This demands a sensitivity to cultural contexts that mere numerical data may obscure.

Moreover, the methodologies and interpretations derived from carbon and radioactive dating are susceptible to the biases and perceptions of the scientists conducting the research. Issues of cultural bias can infiltrate the interpretations of data, where the value placed on certain artifacts may skew historical narratives, thereby shaping contemporary understandings of identity and heritage. The power of archaeological findings lies not only in their physical presence but also in the stories they enable, often influenced by prevailing cultural ideologies.

The implications of radioisotope dating extend into the realm of public discourse and policymaking. As societies grapple with heritage preservation and the impact of colonial histories, the scientific authority of dating techniques can either empower or disempower marginalized communities. For example, decisions regarding land rights, museum displays, or cultural patrimony hinge upon interpretations of archaeological data. The seemingly objective nature of carbon and radioactive dating can mask underlying subjective dimensions that reflect power dynamics embedded within cultural narratives.

As societies become increasingly interconnected through globalization, the narrative of time derived from carbon and radioactive dating also intersects with broader anthropological discussions about the implications of technological advancement and environmental changes. Challenges such as climate change necessitate that our understanding of cultural timelines extends beyond mere historical curiosity; they urge a reevaluation of human engagement with nature over millennia. The interplay of scientific discovery, social constructs, and environmental stewardship exemplifies how carbon and radioactive dating are not just scientific inquiries, but societal dialogues that shape and redefine the human experience.

In conclusion, while carbon dating and radioactive dating are essential scientific methodologies, their implications are far-reaching, touching upon cultural perceptions of time, history, and identity. The interplay between scientific knowledge and cultural relativism frames the ongoing discourse about how we measure history and the significance attributed to our past. Understanding that these techniques operate within a broader sociocultural spectrum urges a reexamination of their roles—not merely as tools for age determination, but as instruments that influence how societies frame their narratives, understand their identities, and confront their futures.