The narrative of the Chinese workers who labored on the transcontinental railroad is a profound testament to perseverance, resilience, and cultural complexity. Their stories, often overshadowed by the dominant historical discourse surrounding the railroad, illuminate not only their contributions but also the struggles they endured. Through the lens of cultural relativism, one can gain a nuanced understanding of their circumstances, values, and the socio-political context that defined their existence in 19th-century America.

In the mid-1800s, the United States embarked on an ambitious project to connect the East and West coasts through a transcontinental railroad. This endeavor was not merely a feat of engineering; it was emblematic of America’s manifest destiny ideology. As the demand for labor intensified, especially amidst the Gold Rush era, Chinese immigrants found themselves at the intersection of hope and desperation, migrating to America in search of better fortunes. Their initial arrival was met with a mixture of opportunity and hostility, reflecting a complex tapestry of societal values and biases.

Upon their arrival, many Chinese immigrants faced daunting challenges. The predominant sentiment among the American populace was one of xenophobia, fueled by prevailing notions of racial superiority. The Chinese workers, often viewed as cheap labor, were subjected to derogatory stereotyping, which positioned them as “the other” in a rapidly evolving American culture. This marginalization was exacerbated by economic strains and competition for jobs, revealing uncomfortable truths about American society’s values of capitalism and individualism, predominantly at the expense of laborers from marginalized backgrounds.

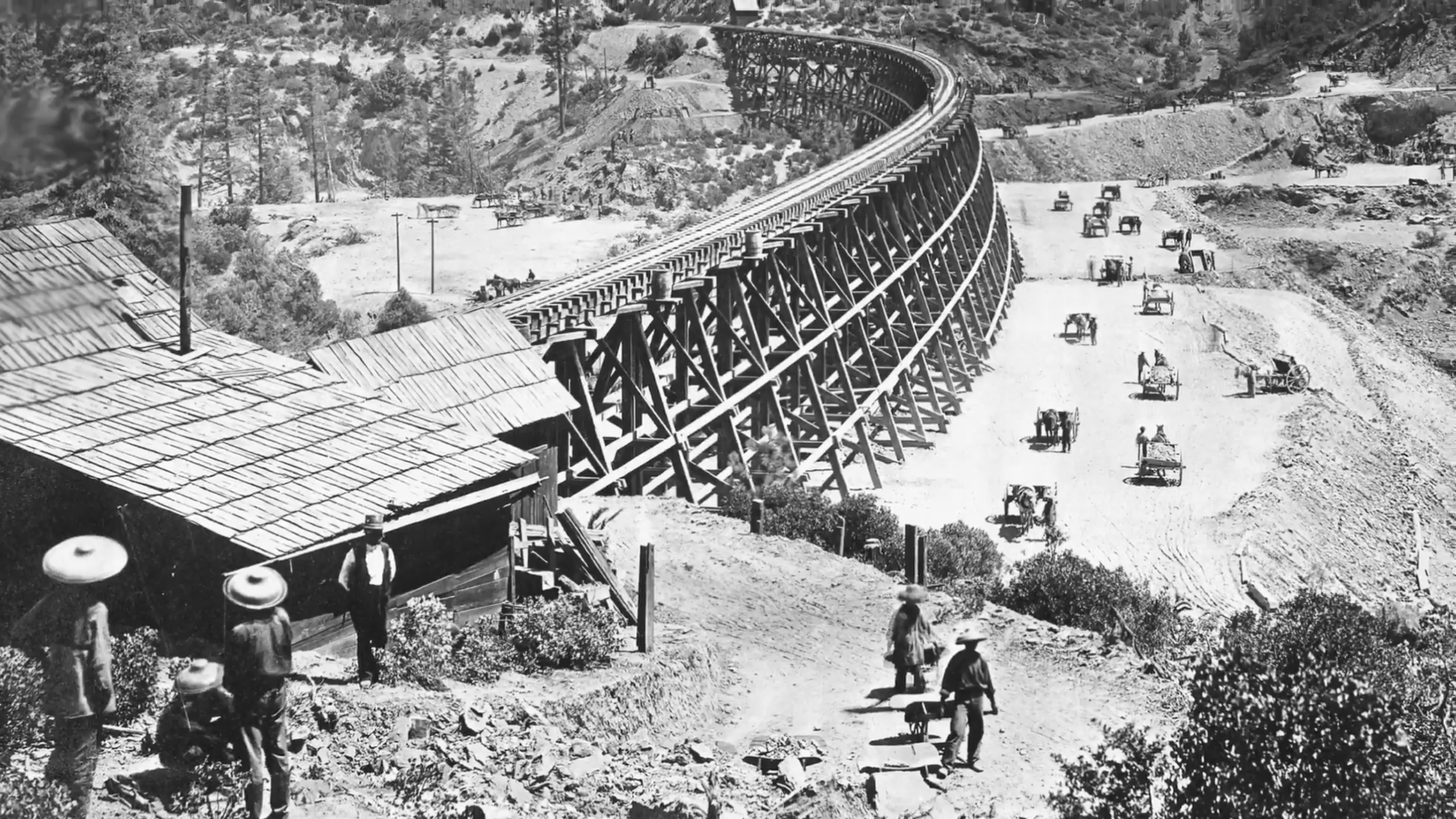

Nevertheless, the contributions of Chinese workers to the transcontinental railroad were indispensable. They undertook some of the most perilous tasks, including blasting through the Sierra Nevada mountains. These projects required not only physical strength but also ingenuity and tenacity. Employing traditional Chinese techniques and tools, these workers showcased a rich cultural heritage. Their labor was a fusion of Western innovation and Eastern tradition. Understanding this synthesis offers a lens through which one can appreciate the value of cultural exchange, particularly in the face of adversity.

Moreover, the labor conditions experienced by Chinese workers were harrowing. They endured grueling hours, perilous working environments, and minimal pay—often receiving half of what their white counterparts earned. The grueling reality of this exploitation starkly contrasts with the romanticized notion of the American dream. However, it is vital to analyze this situation through a cultural relativism perspective, which posits that one must understand a culture’s practices and challenges within their specific socio-historical context, rather than viewing them through a restrictive lens of contemporary moral standards.

Cultural relativism challenges us to consider the complexities of the workers’ experiences. Despite facing ruthless exploitation and dehumanization, the Chinese workers fostered community solidarity. They created support networks, cultural rituals, and social organizations that provided a semblance of normalcy amidst chaos. Festivals, religious practices, and communal gatherings served as crucial mechanisms for preserving cultural identity. These social structures played a significant role in shaping resilience, allowing them to navigate the hostile environment while maintaining a connection to their roots.

The eventual completion of the railroad in 1869 marked not only a significant engineering triumph but also a bittersweet moment for many Chinese laborers. Their contributions to the construction of this monumental infrastructure were largely unrecognized in the annals of history, reflecting a broader pattern of erasure faced by immigrant communities. Despite their integral role, the narrative surrounding the completion of the railroad predominantly celebrated the efforts of white railroad magnates, while the voices of Chinese workers remained largely silenced.

This lack of acknowledgment is a glaring example of cultural hegemony—where dominant narratives overshadow and marginalize the experiences of minority groups. Delving into the historical discourse surrounding the railroad offers a critical opportunity to explore the dynamics of power, identity, and representation. Understanding the Chinese workers’ plight necessitates an examination of how cultural narratives are constructed and who benefits from their dissemination.

In the aftermath of the railroad’s completion, the environment shifted further for Chinese immigrants. Anti-Chinese sentiment escalated, culminating in discriminatory legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which severely restricted Chinese immigration and afforded few rights to those already residing in the United States. This policy not only exemplified systemic racism but also underscored the precarious position of Chinese workers within the socio-economic hierarchy of America.

Conclusively, the stories of Chinese workers on the transcontinental railroad transcend mere historical accounts; they represent a microcosm of the broader immigrant experience and raise pertinent questions about resilience, identity, and societal values. Through the lens of cultural relativism, these narratives reveal the intricate dynamics of power, the role of community in adversity, and the profound significance of cultural identity amidst oppression. It serves as a reminder that understanding history requires grappling with uncomfortable truths and recognizing the multifaceted nature of human experiences.

Ultimately, to commemorate the contributions of Chinese workers, we must not only reclaim their narratives but also advocate for an inclusive historical discourse that recognizes their integral role in shaping America’s infrastructure and societal fabric. Their courageous stories of struggle and tenacity deserve acknowledgment, respect, and integration into the broader narrative of American history.