In the grand tapestry of human history, the era in which Jesus lived offers profound insights into the quotidian lives of individuals, particularly through the lens of clothing. This exploration delves into the socio-cultural and economic fabric of the time, examining clothing as a prism through which one can discern the complexities of identity, status, and belief systems prevalent in Judea during the first century. By understanding clothing in the time of Jesus, we can foster a deeper comprehension of cultural relativism and appreciate the multifaceted nature of human expression in a historical context.

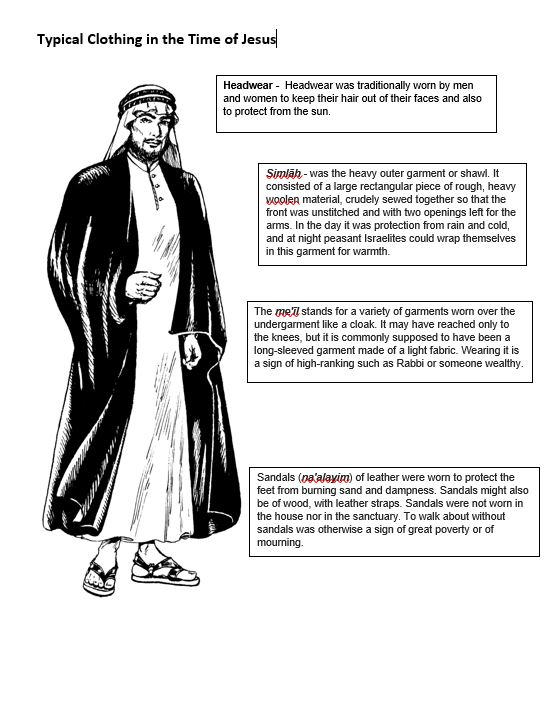

The climate of Judea is paramount in understanding the clothing choices of its inhabitants. Characterized by a Mediterranean climate, the region experienced hot summers and mild winters. Typical garments, therefore, were designed for practicality, utilizing lightweight fabrics such as linen and wool to accommodate comfort as well as mobility. The tunic, a fundamental piece, served multiple purposes—it was adequate for work, yet could be adorned for more formal occasions. This duality exemplified the intrinsic relationship between clothing and one’s socio-economic status, as higher-quality tunics signified affluence and social standing.

Accessibility to raw materials further influenced clothing in this era. The burgeoning textile industry was evident in Jerusalem and surrounding areas. Natural dyes derived from plants were utilized, yielding vibrant colors; however, the relative cost associated with these dyes often meant that only the wealthier classes could afford garments adorned in striking hues. The commoners, conversely, usually donned earth-toned attire, reflective of their lower socio-economic stature. This disparity in textile choices acted as a visual manifestation of social hierarchy, illustrating how clothing was not merely functional but laden with meaning.

Moreover, the act of dressing was also steeped in cultural and religious symbolism. Jewish law, as delineated in the Torah, provided stringent guidelines concerning attire. The commandment to wear tzitzit, tassels on the corners of garments, underscores the mandate to remember and observe one’s covenant with God. This aspect of adornment extends far beyond aesthetics; it intertwines with faith and identity, revealing the interplay between personal expression and religious duty. In this way, clothing transcends mere utility, offering insight into the semiotic landscape of the period.

Fashion, too, served as a repository for the prevailing zeitgeist. The Roman occupation introduced new cultural influences that permeated various aspects of life, including clothing. Roman attire, such as the toga, began to make inroads into the local fashion landscape. The adoption or rejection of these external influences can be viewed through the lens of cultural relativism, which posits that one must understand cultural practices within their own context rather than through the lens of differing customs. In this environment of cultural exchange and convergence, the Judeans practiced selective assimilation, incorporating elements of Roman fashion while simultaneously preserving their unique identity.

Additionally, gender played a critical role in the realm of fashion. Men and women adhered to distinct sartorial standards, with women’s clothing often symbolizing modesty and virtue. The garments worn by women, typically longer and more layered, further reinforced societal norms regarding femininity. Conversely, male garb tended to be simpler, reflecting the pragmatic nature attributed to masculinity. Yet, one must approach these gender norms with an understanding of their historical context, recognizing that the binary interpretations of gender and attire have evolved significantly over time.

In exploring the nuances of clothing during this period, it is essential to consider the socio-political turbulence that characterized the era. The Jewish Revolt against Roman rule (66-73 CE) served as a crucible for national identity. During this time, clothing became an emblem of resistance. The redrawing of identity through attire illustrated how clothing functioned as a visual declaration of solidarity among the Jewish populace. Thus, while clothing served practical purposes, it simultaneously became a canvas for resistance, allegiance, and cultural pride.

Artifacts from this period, including pottery and frescoes, echo the narratives woven through clothing. These remnants allow modern scholars a glimpse into the sartorial behaviors of that time, providing context for the ways clothing articulated identity and status. Each artifact is a testament to the dynamic interplay of daily life, cultural tradition, and personal expression. These historical vestiges challenge scholars to reassess the potential meanings imbued in clothing, urging consideration of the confluence of locality, spirituality, and resistance.

Yet, as we dissect these sartorial elements, an imperative emerges: to appreciate the complexities of cultural relativism in our understanding of historical narratives. Clothing serves as a microcosm of broader societal structures, revealing inequities, aspirations, and transformations. The attire of Jesus and his contemporaries invites critical inquiry into how daily objects inform our interpretations of history.

In summary, the examination of clothing in the time of Jesus transcends mere historical record-keeping; it delves into the very essence of human experience. Through the prism of attire, we discern the lived realities of the past, enriched by cultural meanings that inform our contemporary understanding of identity. The sartorial choices of this era compel us to grapple with the fluidity of cultural expression, urging us to appreciate the myriad ways humans have sought to convey their beliefs, identities, and allegiances. Ultimately, this exploration not only honors the past but enhances our grasp of the present, illuminating the interconnectedness of cultural practices through time and space.