Life expectancy is a concept laden with social, cultural, and economic implications. In 1850, when the average life expectancy in many parts of the world hovered around the forties, reaching age forty was a significant milestone that held various meanings in different cultures. This circumstance would inspire further inquiry into the cultural relativism surrounding age, mortality, and societal norms. Understanding these historical perspectives offers insight into contemporary values concerning aging and life.

To appreciate the cultural connotations of aging in 1850, one must first comprehend the global context. Industrialization was reshaping economies and lifestyles, especially in the West, while vast populations in various regions faced different challenges impacting health and longevity. In agrarian societies and nascent urban centers alike, the harsh realities of sustenance and survival significantly affected the population’s vitality. Factors such as disease, malnutrition, and poor living conditions rendered life expectancy rates perilously low.

In societies where life expectancy was markedly short, the interpretation of aging diverged greatly from modern sensibilities. Reaching forty was not merely an indication of age but often a testament to resilience. Elders were venerated in many cultures as they embodied the societal accumulation of knowledge and experience, a stark contrast to contemporary views that sometimes equate youth with value. In this light, cultural relativism becomes crucial; a person’s worth in society was once intricately tied to age and experience rather than mere physical vitality. Aged individuals were often consulted for their wisdom and understanding of communal affairs.

The notion of age was also deeply entwined with societal roles. In various cultures, the transition to elder status came with increased responsibility and authority. For instance, among Indigenous peoples, elders often governed decision-making processes, guiding younger generations with teachings passed down through centuries. This respect for the elderly underscores a broader cultural paradigm where age is revered and celebrated, contrasting with contemporary views that may perceive aging as an affliction or period of decline.

Notably, cultural attitudes toward aging were marked by spirituality and existential contemplation. Many societies harbored beliefs tying aging to spiritual maturity or the manifestation of life cycles. In many religious and philosophical traditions, reaching an advanced age was seen as a potential gateway to an enlightened understanding of life and death. In this sense, cultural perspectives on aging incorporated metaphysical dimensions that transcended the mere biological aspects of life expectancy.

Addressing the biological determinants behind life expectancy reveals a host of factors that shaped the lived experiences of individuals. In 1850, common ailments such as tuberculosis, cholera, and smallpox plagued populations, decimating lives before the age of forty. The lack of modern healthcare interventions rendered many diseases fatal. Cultural practices, such as dietary customs and medical traditions, also influenced individual longevity, leading to varying experiences across regions. In certain societies, dietary restrictions based on religious tenets, such as vegetarianism among Hindus or the kosher dietary laws in Judaism, may have contributed to healthier lifestyles, thereby affecting life expectancy rates in those demographics.

Additionally, socio-economic disparities played a crucial role in shaping life expectancy across different cultures. Wealthier individuals often had access to better nutrition, sanitation, and medical care, which translated into longer life spans. In contrast, marginalized groups suffered disproportionately from poor living conditions, leading to premature mortality. Consequently, one must consider the intersectionality of class, ethnicity, and geography when examining life expectancy as a cultural construct, as these factors created an uneven landscape of health outcomes.

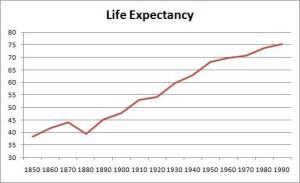

Furthermore, as life expectancy began to increase toward the end of the 19th century, the implications on social structures became pronounced. With the advent of improved public health measures, sanitation systems, and medical advancements, populations began to live longer. This newfound longevity began to blur the lines between age and wisdom, leading societies to reevaluate their cultural constructs surrounding the elderly. Once revered figures faced a reality where their societal roles could become ambiguous in a world that increasingly valued productivity over age-old traditions.

Therefore, the concept of age in 1850 must be understood in a multifaceted context, wherein biological, cultural, spiritual, and socio-economic elements interweave to create a rich tapestry of human experience. Each of these factors not only influenced life expectancy but also shaped the entire societal narrative regarding aging. The observation that forty was considered old in that era indicates not just a numerical reality but a culmination of historical and cultural significances that resonate through time.

In conclusion, examining life expectancy in 1850 within the framework of cultural relativism unveils a deeper understanding of how societies interpret age and mortality. While contemporary perspectives may often prioritize youthfulness and vitality, historical viewpoints remind us that each life stage carries its own strengths and values. Ultimately, understanding the cultural nuances surrounding aging offers a more profound appreciation for the diverse meanings that life expectancy may hold across time and space.