The Paleolithic Era, often referred to as the Old Stone Age, spans an extensive time frame, from approximately 2.6 million years ago until around 10,000 BCE. This epoch is characterized not only by the development of early human societies but also by the diverse fauna that inhabited the Earth during this period. To truly appreciate the significance of the animals that roamed alongside early humans, it is essential to examine this era through a lens of cultural relativism. Such an approach enables a more nuanced understanding of how these creatures were perceived, utilized, and revered across various early human cultures.

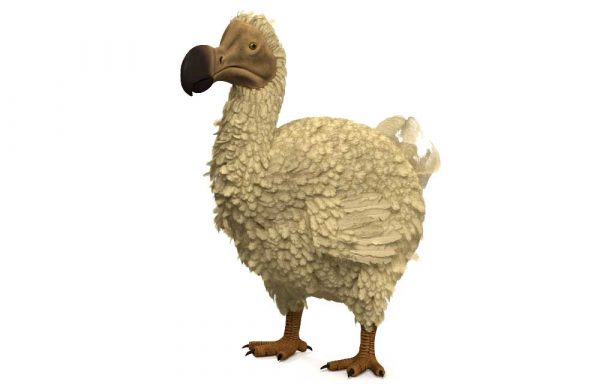

The complexity of life during the Paleolithic Era can be understood through a survey of the megafauna that dominated these landscapes. Generically identified as ‘megafauna,’ these sizable animals include the woolly mammoth, saber-toothed cat, and mastodon. However, their contributions to ecosystems and their roles in the cultures of prehistoric humans extend beyond mere biological classifications. For early humans, these species were not only sources of sustenance but also symbols interwoven with spiritual beliefs and cultural practices.

Megafauna like the woolly mammoth became particularly significant for early human societies that depended upon them for food, clothing, and materials for shelter. Cultural representations in the form of cave paintings indicate that these creatures were not merely prey but were imbued with cultural importance. The hunting of megafauna may have held ritualistic significance, emphasizing a shared communal identity and reinforcing social cohesion among band groups. This anthropocentric view illustrates how survival required no small amount of reverence towards the non-human entities with which early humans coexisted.

The human-animal dynamic in the Paleolithic Era can also be expounded upon through the context of totemic relationships. Many early societies likely perceived certain animals as totems or spirit guides, embodying cultural ideals or providing wisdom. In a cultural relativist view, these perspectives invite a reinterpretation of hunting practices. The act of hunting a woolly mammoth might not solely be seen as a struggle for survival but also as an encounter imbued with spiritual significance, where the hunter must demonstrate respect for the creature’s spirit in a bid for success. This emphasizes a symbiotic relationship rather than a purely exploitative one.

However, the interactions between early humans and the megafauna they hunted were not devoid of consequences. The extinction of many megafauna species during and after the Paleolithic Era raises questions about the impact of early human activities on these colossal creatures. Cultural relativism allows for an exploration of various viewpoints regarding these extinctions. Some ancient cultures might have perceived the decline of megafauna populations as a natural cycle, while others may have interpreted it as a manifestation of divine disfavor or punishment, which could have driven them to alter their hunting practices or adapt their lifestyles accordingly.

Furthermore, this era is pregnant with the symbolism associated with predatory animals like the saber-toothed cat. Human adaptation and survival strategies hinged upon the recognition of these apex predators within their ecosystems. The cultural portrayal of such animals in art, from cave paintings to carvings, represents an early form of storytelling, embodying fear and admiration alike. Through a culturally relativistic lens, the formidable image of the saber-toothed cat invites discourse on how such creatures influenced narratives, metaphors, and even morals within early human societies.

The adaptability of early humans in the Paleolithic Era can be attributed not only to their ingenuity but also to their intricate understanding of their environment. They observed animal behaviors, migratory patterns, and breeding cycles, allowing for a more sustainable approach to hunting and gathering. Such knowledge was not universally inherent but shaped by geographical and cultural contexts, exhibiting variations across different bands and tribes. This presents an opportunity to examine the relationship between cultural practices and ecological knowledge, showcasing the sophistication behind what could be perceived as primitive existence.

The rich tapestry of life in the Paleolithic Era also included smaller fauna such as rodents, birds, and various species of fish. These animals played a critical role in the diets of early humans and offered ecological stability. A cultural relativist perspective allows us to consider how different groups interacted with these animals — whether for subsistence, symbolism, or both. Capturing the escoteric nuances of these interactions leads us to appreciate the diverse tapestry of beliefs, practices, and survival strategies that characterized Paleolithic societies.

Art from this era, epitomized by cave paintings, serves as a testament to the interconnectedness of Paleolithic humans with their environment, serving both practical and existential roles. The act of depicting animals underscores a form of communication — a narrative that speaks to the human condition. Curiosity towards the cosmos, existence, and the natural world blooms through these early artistic expressions. This interest evokes an appreciation for how early cultures endeavored to frame their reality within the parameters of their lived experiences.

In conclusion, the study of life in the Paleolithic Era necessitates a cultural relativist perspective to unearth the depths of human-animal relationships that shaped early societies. The ecological interplay between megafauna and early humans is a prime illustration of the complex dynamics at play. Through a critical lens, one can appreciate that these connections were not merely transactional but rich with cultural, spiritual, and existential significance. As we reflect on the Paleolithic Era, it is imperative to acknowledge the wisdom embedded in the coexistence of humanity and the magnificent creatures that once roamed the Earth, inviting us to understand our place within the broader narrative of life itself.