Moral philosophy endeavors to navigate the intricate territories of rightness and wrongness, guiding humanity in its ethical quandaries. Two dominant paradigms in this discourse are moral relativism and moral absolutism. These frameworks frame our understanding of morality, influencing not just individual decisions but also societal norms and legal statutes.

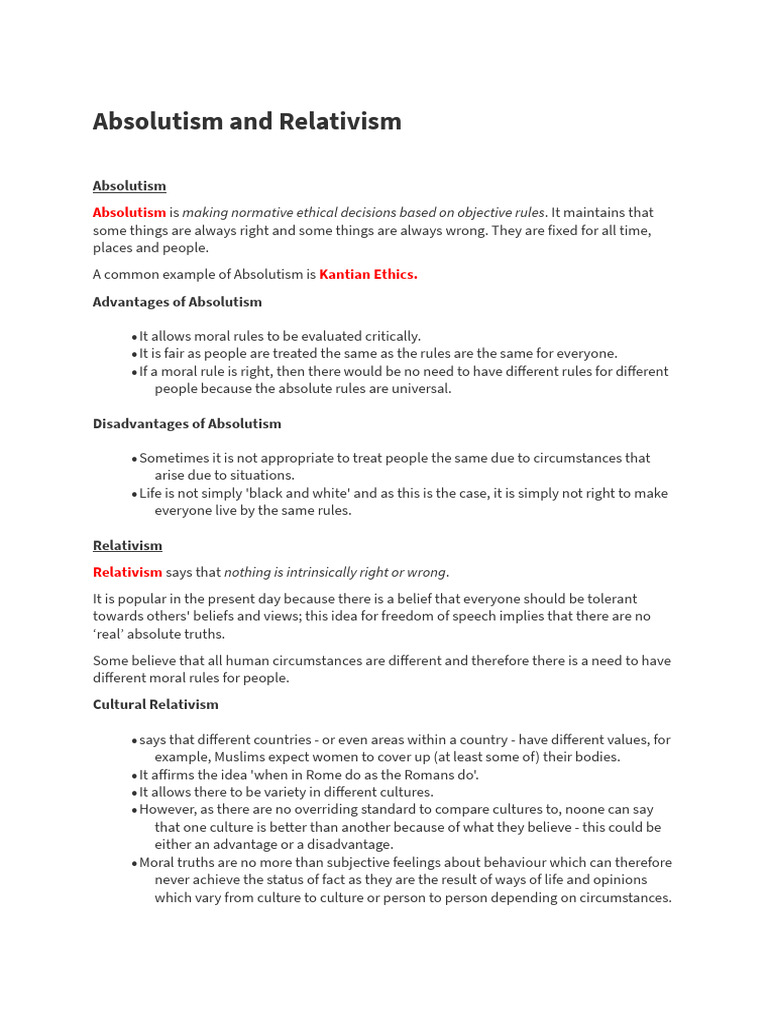

Moral relativism posits that moral judgments are contingent upon cultural, societal, or personal contexts. In this view, what is considered “right” in one society may be deemed “wrong” in another. For instance, practices such as polygamy, which are accepted in certain contexts, could be condemned in others based solely on differing cultural interpretations. This perspective is grounded in the belief that no universal standards govern morality; instead, ethical norms evolve with the fabric of society.

A salient advantage of moral relativism is its promotion of tolerance and understanding. By acknowledging that diverse cultures harbor different moral frameworks, relativism encourages dialogue among varying belief systems. This aspect is particularly relevant in an increasingly globalized world, where interactions among divergent cultures are commonplace. As individuals encounter practices that differ from their own, relativism can foster an appreciation for alternative views, countering ethnocentrism.

However, moral relativism is not without its pitfalls. Critics argue that it fosters a kind of ethical paralysis. If morality is entirely context-dependent, it becomes challenging to critique harmful practices. For example, oppressive systems, such as slavery or caste discrimination, might be justified under the guise of cultural norms. This raises a critical question: can immoral acts ever be excused simply because they are normatively accepted within a culture? Moral relativism, thus, walks a precarious line between promoting tolerance and permitting grave injustices.

In stark contrast, moral absolutism asserts that there are universal moral principles that transcend cultural or contextual boundaries. This paradigm argues for an objective moral law, often derived from philosophical, religious, or ideological foundations. For instance, many absolutists might contend that acts such as murder or torture are intrinsically wrong, regardless of cultural interpretations. This belief imbues moral absolutism with a prescriptive power that seeks to guide human conduct according to immutable ethical standards.

One of the primary strengths of moral absolutism is its capacity to provide clear ethical guidelines. The unequivocal nature of absolute moral laws offers individuals and societies an anchor in tumultuous moral landscapes. This is particularly beneficial when navigating complex issues such as human rights, where a collective commitment to certain absolutes can catalyze social progress. The civil rights movement, for example, drew heavily upon absolute principles of equality and justice, galvanizing collective action against oppressive structures.

Nonetheless, moral absolutism is not immune to criticism. Detractors question the feasibility of defining universal moral principles that resonate with diverse cultural beliefs and experiences. The imposition of a singular moral framework can lead to paternalism, where dominant cultures undermine or erase the ethical systems of marginalized communities. Moreover, moral absolutism can engender dogmatism. This inflexibility may hinder constructive discourse, as adherents may become resistant to alternative viewpoints or evidence that challenges their stance.

The juxtaposition of these two frameworks invites a fertile discussion regarding the nature of morality. Scholars often explore middle grounds, proposing contextual moral frameworks that retain certain universal principles while allowing for cultural variations. The concept of “global ethics” seeks to balance relativism and absolutism, advocating for a set of fundamental human rights that acknowledge cultural contexts without sacrificing core moral tenets. This approach aspires to create a cohesive ethical landscape amid the cacophony of differing beliefs.

To further elucidate the dialogue surrounding moral relativism and absolutism, consider the realm of environmental ethics, an increasingly relevant aspect of moral philosophy. As climate change looms large, differing cultural attitudes toward the environment illustrate the tension between these two paradigms. In some cultures, a deep connection to nature informs ethical decisions, leading to sustainable practices. Conversely, in others, economic development often takes precedence, even at the expense of environmental degradation.

This divergence raises poignant ethical questions concerning global responsibility. Do nations or corporations hold a moral obligation to prioritize ecological integrity over profit, despite their cultural or economic contexts? A moral absolutist might argue affirmatively, insisting on universal responsibility to protect the planet. Conversely, a moral relativist might contend that responses to environmental challenges must be grounded in cultural realities, thereby allowing for various interpretations of ecological stewardship.

Through this discourse, it becomes evident that navigating moral debates requires a nuanced understanding of both relativist and absolutist perspectives. Each framework carries unique implications, influencing not only individual decision-making but overarching societal norms and legal structures. As humanity grapples with complex ethical dilemmas, recognizing the interplay between these schools of thought becomes essential. Achieving a synthesis that values cultural diversity while championing fundamental ethical standards may ultimately guide society in forging a more just and sustainable future.

In summation, moral relativism and absolutism, with their distinct yet intertwined philosophies, offer valuable insights into the understanding of ethics. Each perspective holds qualities that can foster meaningful dialogue and societal growth if we approach them thoughtfully, striving for a more enlightened moral landscape where ethical plurality is embraced yet anchored by common human values.