The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, known formally as linguistic relativity, encompasses an intriguing proposition that language intricately shapes our cognition and perception of reality. This hypothesis posits that the structure of a language affects its speakers’ worldviews. The premise raises essential questions about how our linguistic frameworks constrain or liberate our cognitive capabilities. But what if linguistic constraints also limit our understanding of pressing global issues, such as climate change? Could it be that those who speak differently about environmental phenomena are fundamentally equipped to comprehend and tackle them in ways that others are not?

First articulated by American linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, the hypothesis delineates two primary notions: linguistic determinism and linguistic relativity. Linguistic determinism asserts that language rigidly determines thought, suggesting that without specific vocabulary or grammatical structures, certain ideas remain ineffable. In contrast, linguistic relativity posits a softer approach, where language influences but does not rigidly dictate thought processes. This nuanced differentiation invites a playful inquiry: does the language we use bolster our ability to address the complexities of climate change, or does it introduce limitations?

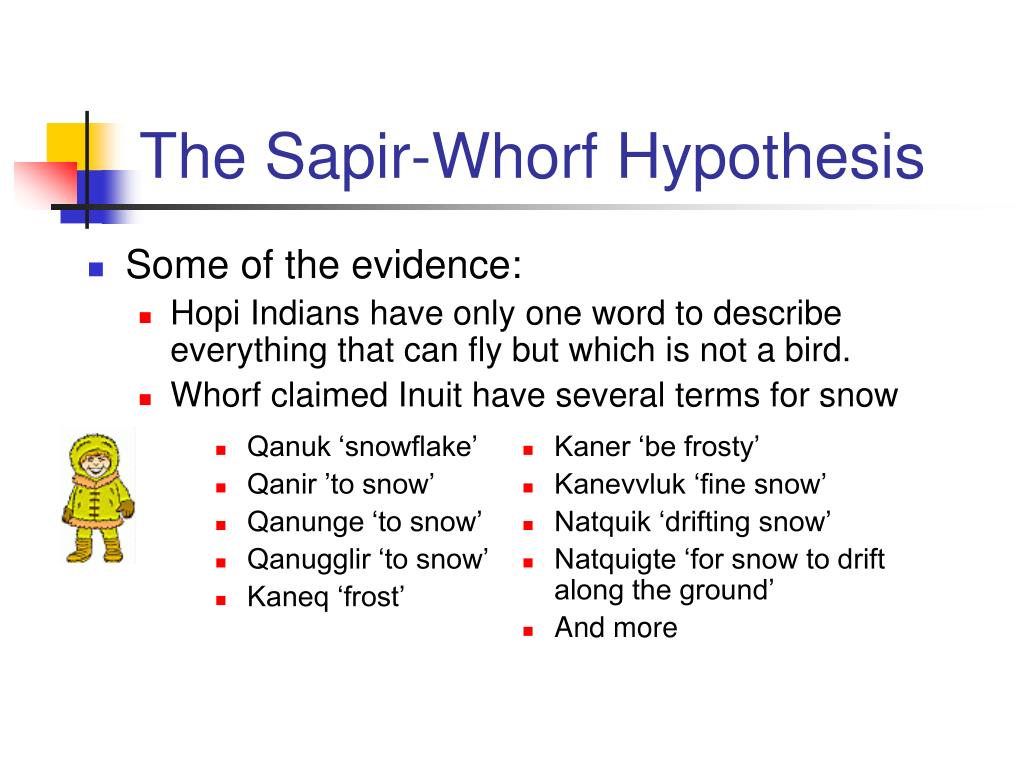

To explore this, one must consider the vast diversity of languages and their idiosyncrasies. For instance, languages such as Inuit possess multiple words for snow, indicating nuanced understanding and differentiation. This could influence speakers’ perceptions and interactions with snow-covered environments. Similarly, languages with an extensive vocabulary linked to ecology and environmental phenomena might foster greater awareness and engagement regarding climate change. Is it conceivable that those who speak such languages possess a more profound connection to ecological concerns compared to those whose languages are less descriptive?

The implications of this hypothesis extend beyond academic curiosity; they are vital for global discourse on climate policy. Consider the lexicon employed in discussions around climate change. In English, terms such as “global warming” and “carbon footprint” serve as rallying points for activism and policy-making. Yet these terms may fail to resonate in cultures whose languages frame environmental relationships differently. If speakers of such languages lack the linguistic tools to articulate their experiences with ecological changes, how does this affect their engagement in global environmental dialogues?

Furthermore, examining the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis necessitates an acknowledgment of the role of culture. Language is not merely a tool for communication; it is a repository of cultural knowledge. Variations in environmental references across cultures arise from distinct cultural experiences and relationships with nature. For instance, certain Indigenous languages encapsulate deep ecological insights rooted in ancestral knowledge. This raises a fundamental query: can our global environmental strategies afford to overlook the cultural contexts shaped by varied linguistic traditions?

A potential challenge arises in translation. As ideas traverse language barriers, nuances frequently dissipate. A phrase in one language may carry connotations and cultural significance that become obscured when rendered into another. In environmental advocacy, when ideas lose their richness, the potency of action may diminish accordingly. How can activists and policymakers ensure that translations remain faithful to original meanings, maintaining their intended impact on audiences unversed in the source language?

Moreover, the discourse surrounding climate change often gravitates toward urgency and alarmism, utilizing language that emphasizes crisis. This can inadvertently alienate audiences who may prefer a more optimistic or solution-oriented narrative. If language influences motivation and perception, then the grammatical constructions and connotative choices made in climate communication are pivotal. This begs the question: can a reframed dialogue surrounding environmental issues in more hopeful, inclusive language catalyze broader collective action?

The interplay between language and thought also connects to the concept of empathy. Research has shown that individuals equipped with a rich emotional vocabulary can express and process feelings more effectively. A similar principle may apply when discussing global climate issues. A language that fosters emotional depth encourages speakers to articulate concerns about their environment more vividly. This invokes the contemplation of whether policymakers should advocate for enhanced emotional literacy in environmental dialogues, potentially creating more empathetic outcomes.

It is essential to recognize that the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does not designate any language as innately superior; rather, it highlights the distinct lenses through which different speakers perceive reality. The challenge lies in perceiving the affective power of language as we craft narratives around urgent environmental predicaments. As populations globally face climate catastrophes, it is crucial to discern the richest linguistic frameworks that propel ecologically conscious action.

Ultimately, while the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis may not provide definitive answers, it opens a Pandora’s box of intriguing inquiries regarding the interplay of language, thought, and ecological awareness. Those engaged in sustainability efforts should remain cognizant of the cultural frames and linguistic subtleties underpinning climate discourse. The playful question posed at the outset—does language enrich or limit our ability to confront climate change?—is one that demands ongoing exploration. Only by examining these interconnections can a more inclusive and impactful dialogue emerge, one that resonates across diverse linguistic landscapes and compels global stewardship of the environment.