The modern Ainu woman represents a confluence of heritage and contemporary identity, encapsulating the richness of the Ainu culture and the complexities posed by globalization and societal evolution. As we analyze this multifaceted identity, an intriguing question arises: How do the striking visual attributes, such as blue eyes, interact with deeper cultural narratives to define what it means to be a modern Ainu woman? The exploration of this topic fields a range of discussions centered on cultural relativism, identity formation, and the impact of societal norms.

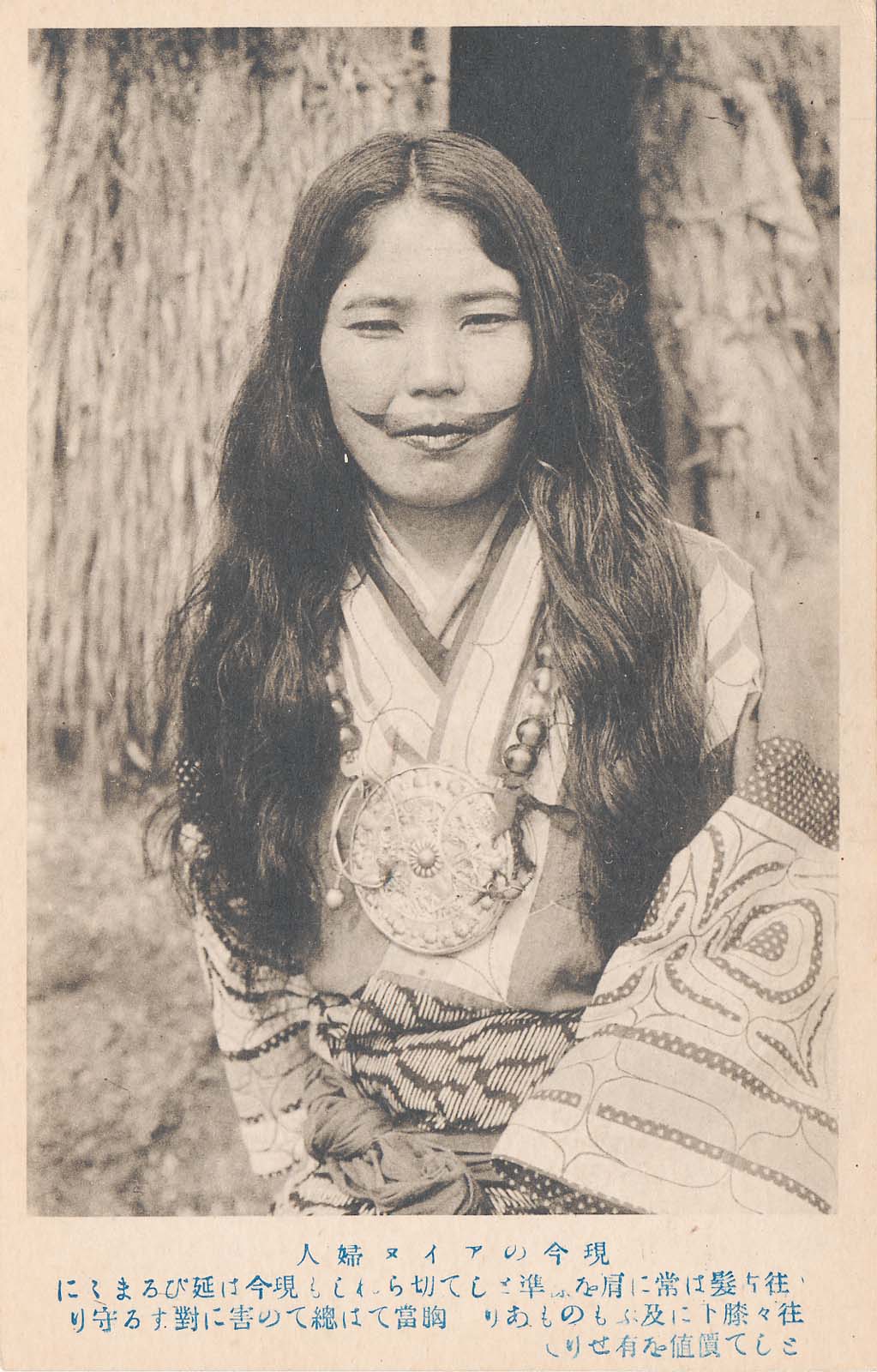

The Ainu are an indigenous people originating from the northern regions of Japan, notably Hokkaido, as well as parts of Russia. Their culture is characterized by unique customs, traditional dress, and a deep spiritual connection to nature. Historically, Ainu women played vital roles in both the domestic sphere and in cultural practices such as textile production and ritual performance. However, contemporary Ainu women navigate a societal landscape rife with challenges, predominantly stemming from assimilation pressures and socio-political marginalization.

In examining the modern Ainu woman’s identity, it is essential to understand the concept of cultural relativism. Cultural relativism posits that one must understand and evaluate cultures based on their own standards, rather than imposing external judgments. This perspective encourages a nuanced understanding of the Ainu’s response to external influences. The blue-eyed phenotype, often perceived as a Western trait, is emblematic in the context of mixed heritage. It raises questions about the assimilation of Ainu identities and how they recontextualize their features within the scope of their cultural narrative.

The Ainu culture places significant emphasis on communal identity, storytelling, and reciprocity with the environment. However, modern pressures have given rise to a juxtaposition between traditional cultures and the globalized world. Women, in particular, are at the forefront of this shift, striving to reclaim their identity while also adapting to contemporary realities. This duality is woven into the fabric of their existence; they embody both the resilience of tradition and the challenges of modernity.

Interactions within society can be observed through the lenses of media and representation. The portrayal of Ainu women in popular culture may romanticize or distort their realities. Such representations often fail to capture the nuances of Ainu women’s daily lives, perpetuating stereotypes that do not align with lived experiences. Therefore, the modern Ainu woman must engage with these representations critically, asserting agency over her identity while navigating societal expectations.

This leads to a potentially contentious challenge: Can cultural authenticity coexist with modern identities? The modern Ainu woman’s journey offers an exceptional case study into this dilemma. On one hand, there is an inherent desire to preserve traditions; on the other, the pressures of contemporary life necessitate adaptation. Within this context, blue eyes serve as a potent symbol. They not only signify a physical characteristic but also represent the intersections of various cultural influences. This embodiment prompts the examination of what constitutes authentic Ainu identity today.

Educating oneself on the Ainu’s art, folklore, and oral traditions illuminates their historical contributions to cultural heritage. Modern manifestations, such as weaving, embroidery, and even performances, evolve continuously but remind the community of their ancestral roots. The modern Ainu women’s engagement with these forms thus becomes a means of preserving culture while simultaneously reaffirming their identities against a tide of assimilation.

Scholars have documented the Ainu women’s efforts to reclaim their narrative in an era where globalization threatens the unique aspects of indigenous cultures. Empowerment initiatives focus on restoring linguistic practices, traditional knowledge, and artistic expression. These endeavors highlight the agency of modern Ainu women as they reimagine their roles both within their community and in a broader global context.

Furthermore, legal and political aspects augment the modern Ainu woman’s identity. The struggle for recognition as an indigenous group in Japan has led to increased awareness and educational initiatives. Women activists, utilizing significant platforms, advocate for social change while emphasizing their unique cultural heritage. This activism embodies a powerful expression of identity, serving both as resistance and renewal of tradition.

In conclusion, the modern Ainu woman occupies a complex and dynamic space characterized by a melange of historical continuity and contemporary challenges. Blue eyes, while simply a biological feature, represent so much more than that. They symbolize the interplay of multiple identities and the conundrum of cultural preservation in an age of globalization. As society continues to evolve, questioning the frameworks through which we understand cultural identity becomes crucial. The modern Ainu woman, with her vibrant heritage and uniquely nuanced experiences, stands as a testament to the resilience of indigenous cultures and the ongoing dialogue between tradition and modernity.

Ultimately, engaging with these themes invites a deeper understanding of cultural relativism, as we learn to appreciate the rich fabric of diversity woven from differing experiences and backgrounds. How does society allow for the coexistence of diverse identities, and what role does the modern Ainu woman play in this ongoing narrative? The continued exploration of such inquiries may illuminate the paths to broader cultural appreciation and understanding, underscoring the importance of both individuality and communal identity in our interconnected world.