Why is it that bonobos and chimpanzees, our closest evolutionary relatives, find themselves incapable of articulated speech, despite their sophisticated social structures and cognitive abilities? This intriguing question invites scrutiny from various perspectives, notably through the lens of evolutionary biology and cultural relativism methodologies. Each vantage point offers a dimension in understanding the intricacies underpinning communication capabilities across species, and it also reveals the limitations inherent in the evolutionary development of articulate language.

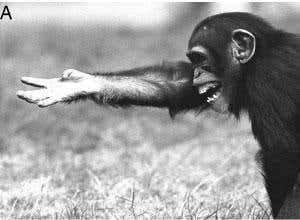

The evolutionary trajectory of Homo sapiens showcases an unparalleled leap in linguistic capabilities—a phenomenon that seemingly eludes our great ape relatives. While bonobos and chimpanzees have developed complex forms of nonverbal communication, such as gestures, vocalizations, and facial expressions, they lack the anatomical and neurological substrata necessary for producing spoken language. This limitation warrants deeper exploration as it raises profound questions about the connections between biology, culture, and cognition.

Primarily, the evolutionary limitations of bonobos and chimpanzees regarding speech can be traced to structural differences in their vocal apparatus. Unlike humans, who possess a descended larynx, bonobos and chimpanzees exhibit a higher laryngeal placement, which restricts the variety of sounds they can produce. The intricate interplay of tongue, throat, and vocal cords in humans allows for an expansive range of phonetic utterances that are critical for speech as we define it. Consequently, this anatomical distinction not only situates our species advantageously in terms of sound production but inherently influences the potential for developing complex syntactic structures characteristic of human language.

Moreover, the neurological architecture governing language processing is significantly more developed in humans than in bonobos and chimps. The human brain harbors regions such as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, which are integral to language production and comprehension, respectively. These areas exhibit heightened neural connectivity and specialization in humans, enabling the intricacies of language that distinguish our species. Current research suggests that while chimpanzees demonstrate underlying neural substrates for communication, these pathways are insufficiently developed to support the grammatical complexity found in human linguistic exchanges.

The challenge posed by these biological constraints raises stimulating questions in the domain of cultural relativism. Can we ascertain that communication potential is strictly a function of biological endowment, or does the cultural context play an equally pivotal role? To adequately analyze this, we must delve into the cultural constructs that underpin human language. Throughout various societies, language functions not merely as a tool for information exchange; it also embodies cultural identity, social norms, and collective memory. Thus, viewing communication through a culturally relativistic perspective reveals that while certain species may be biologically predisposed to limit their speech, each species has developed tailored communication systems that serve their environmental and social needs.

This approach illuminates how bonobos and chimpanzees employ alternative communication methods that may sufficiently fulfill their social and environmental requirements. For instance, the gestural communication observed in these species showcases a rich lexicon of signs tailored to convey emotional states, social hierarchies, and relational dynamics. Such gestures are imbued with cultural significance and reflect the social structures within bonobo and chimp communities. Therefore, while bonobos and chimps lack spoken language, their forms of communication are not inherently inferior; rather, they represent a different evolutionary strategy tailored to their ecological and social contexts.

In attempting to reconcile the evolutionary limitations of bonobos and chimpanzees with the complexities of human language, it is crucial to contemplate the role of social environment in shaping communicative capabilities. An inquiry arises: would bonobos and chimpanzees develop a form of spoken language if raised in a context that necessitated it? This thought experiment challenges us to consider the malleability of communication and the influence of cultural factors on its evolution. A social environment where both vocalization and complex symbol-based language were essential might unlock latent capabilities in these species, suggesting that culture plays a vital role in language emergence.

Transitioning from this consideration, we must also recognize the potential ethical implications of exploring language capabilities in our closest relatives. The intrinsic value of understanding bonobo and chimp communication systems imbues them with their own legitimacy, independent of human-centric standards. Thus, comparisons based solely on linguistic capabilities risk oversimplifying the rich tapestry of communication that exists in the animal kingdom. Rather than viewing communication as a binary construct—where speech is preordained as superior—one can appreciate an expansive continuum of communicative behaviors that embody both function and significance.

It is essential to emphasize that the limitations faced by bonobos and chimps should not lead to anthropocentric assumptions regarding intelligence and adaptability. Intelligence manifests in diverse forms and capacities suited to an organism’s ecological niche and social requirements. Bonobos manifest emotional intelligence, negotiating social relationships and conflicts with a nuanced understanding of their social matrix. They utilize their communicative strategies to forge alliances, cultivate community bonds, and manifest empathy—functions that are key to their survival and group dynamics.

In conclusion, the inability of bonobos and chimpanzees to engage in spoken language is a multifaceted issue intricately woven into the fabric of evolutionary biology and cultural relativism. Examination of the anatomical and neurological limitations highlights the biological underpinnings of communication, while cultural relativism urges us to appreciate the varied forms communication takes across species. Through this lens, the understanding of linguistic capability transcends simplistic binary frameworks, allowing for greater appreciation of the myriad ways cognition and communication intertwine within diverse ecological contexts. The lesson here is not just about what is lacking in bonobos and chimps, but rather an invitation to celebrate the diversity of communication in the realm of life on Earth.